These resources (which include the content from the book, and where appropriate, downloadable tools) are only available to folks who have purchased the book. Get in touch if you’d like access.

Write it down. Write it down!

Teams often begin work without clear alignment on fundamental questions about their purpose, scope, and ways of working. This ambiguity leads to confusion about priorities, decision rights, and responsibilities. While everyone may feel busy, the lack of shared understanding means efforts aren’t necessarily focused on what matters most.

Therefore…

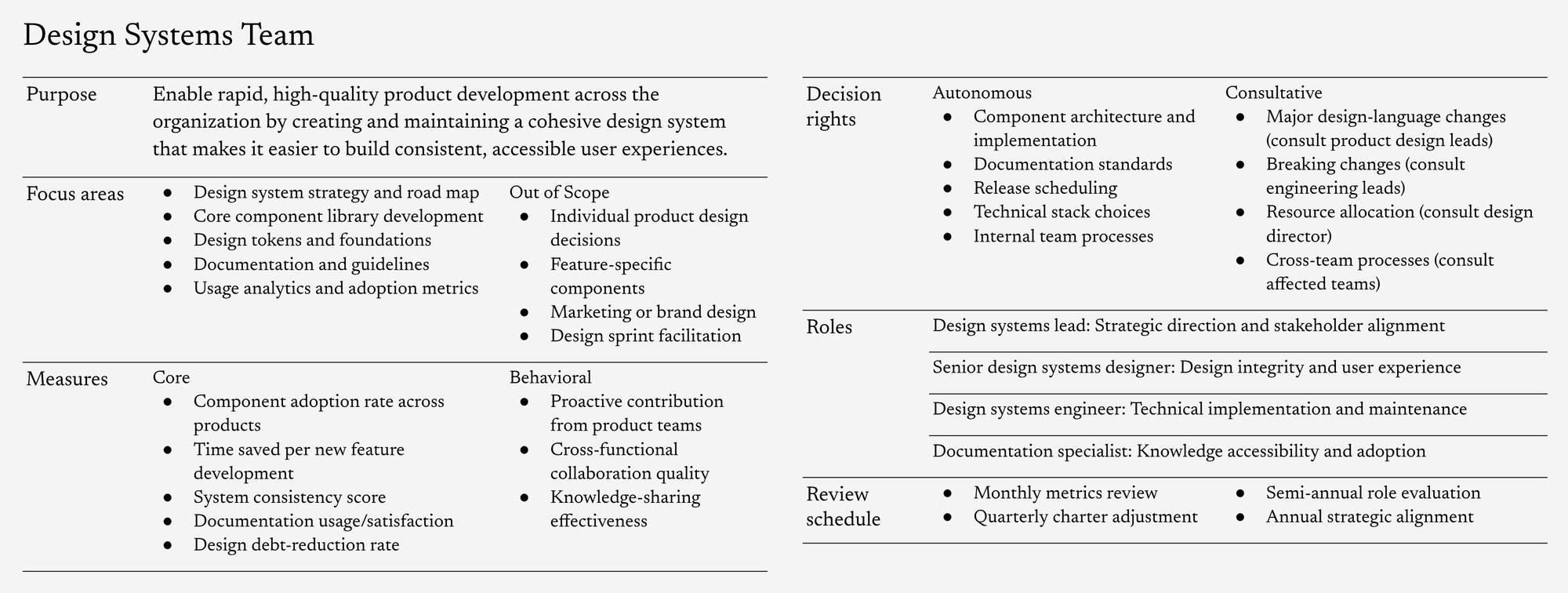

Create a clear team charter that explicitly defines five key elements:

1. true purpose (1)

- Why does this team exist?

- What unique value do we create?

- What would be missing if we didn’t exist?

2. Focus Areas

Including strategy heuristic (29)

- What specific work will we do?

- What are our key priorities?

- What is explicitly out of scope?

3. Measures

Like objectives & key results (28) or relative targets (33) and assessed via metrics review (36); used to apply team incentives (25)

- How will we know if we’re successful?

- What company metrics matter most to us?

- What behaviors do we want to encourage for ourselves? For the organization as a whole?

4. Decision Rights

Including domains, assets & standards (23)

- What decisions can we make without anyone else’s permission?

- Where do we need to consult others?

- What are our key dependencies?

5. Roles

Referencing distributed management (14), and including upward representation (24). Filled via elections (15) and used by the talent marketplace (20).

- What distinct roles do we need?

- What are their core accountabilities?

- How does this role interact with others on our team? With others outside our team?

It’s a good idea to craft the team charter with the team that it governs. Begin with a focused workshop lasting two to three hours where the team collaboratively drafts each section. Use facilitation (56). Ask different team members to lead the discussion of different sections to build shared ownership. Test the charter by applying it to recent decisions or challenges—would it have provided clear guidance?

Review the charter on a specified cadence (65) to ensure it remains relevant. Make updates based on what you’ve learned about how the team actually works. Share the charter with key stakeholders and use it to onboard new team members; work in public (50) so that others can find your charter easily and understand what your team does and does not do.

If you’re starting from scratch, you’ll want to run a small workshop with your team to create your charter for the first time.

Step 1: Get clear on the purpose for the team

This works best if you have a clear, consequential true purpose (1) for the team. Especially in larger organizations, teams don’t have permission to write their own purpose, so doing this prep may require going to the next level of authority in the organization above the team and asking them for clarity on mission. Use the prompts above when thinking about your purpose.

Step 2: Capture the work to be done

Write down all of the work that the team needs to do (not just what it’s doing today) in order to achieve the mission. Try to break down the work to a task level. As an example, “Scheduling flights for vendor assessment” is better than “Travel,” and “Selecting which content gets presented to execs” is better than “Exec decks.”

When you do this right, you’re going to have a lot of tasks. The best tool we have for capturing a team’s full scope of work is a spreadsheet—not Post-its or Miro boards. You’re looking for ease of manipulation—clustering things, tagging things, adding richer data to a bunch of tasks at once—and spreadsheets make this dead simple. A Google Sheet is best, but a Notion database, or Airtable base will work well; the key here is something that many people can edit together in real time. Ideally, assign this prep work to each individual person on the team, and have them put all of their individual work in a single document. It’s easier to cover all the ground on this task when you have a bit of space to think by yourself.

Especially for the corporate teams out there, there are a handful of “kinds of tasks” that you don’t want to forget. Use these as prompts when you’re capturing work:

- What do we do to serve our customers?

- What work is required to guide other teams or direct reports?

- What goes into our team’s partnership with other firms?

- How do we surface data to leadership?

Step 3: Group the work into roles

If you’re working in a spreadsheet, the fastest way to do this is to go row by row and tag each work element with a brief handle. This is where you can start using broader terms like “Travel” or “Exec Decks.” When you’re done tagging, do a quick alphabetical sort based on the row that contains all the tags. Patterns should emerge.

If you want to do this as an in-person workshop, transpose everything from the shared spreadsheet onto Post-it notes and ask the group to cluster related work. Consider clustering based on customer type, functional category, or required expertise. Patterns should emerge.

After you’ve tagged or clustered, you need to name each group. Once you name these clusters, you’ve got your starting set of roles. Naming roles is probably worth breaking down in a separate guide—semantics are important!—but to start, try using a pattern that begins with [Function/Capability/Workstream] and ends with [Style or Involvement]; Finance Guide; Strategy Adviser; Partner Liase-er; etc.

Step 4: Add meaningful definition to the roles

To start, just rewrite the rows in the spreadsheet to follow a common format, where each row begins with a verb. These form the starter set of expectations for the roles you just named.

Some of the expectations will begin with a very special verb: deciding. Look out for these—they can form the backbone of clear decision rights on the team. When you assign one of these expectations to a role, try actually letting that role make the call for a short while, rather than trying to involve everyone on the team.

Step 5: Assign people to the roles

Allow multiple people to fill a single role, and allow individual people to fill a variety of roles. This makes each individual role, and each individual expectation, a little less important—and a little more collective. This is good up to a point: It encourages a more robust discussion of what’s actually important for the team, but can lead to if it’s everyone’s job, it’s nobody’s job-itis. When you notice the latter creeping in, take that as an invitation to break down a role a bit further to get more specific about authority and accountability.

On a traditional team, where there’s a clear team lead, this is the moment for the leader to step forward and use their positional authority to assign people to roles. It can be helpful to set a reasonable time limit to these assignments. Try quarterly time limits to start.

Send me a receipt showing that you pre-ordered the book, and then sign in. You'll get a magic link and then all these chapters are yours to read.