Why Nothing Gets Done Around Here

Hundreds of thousands of hours are getting wasted on bad decision-rights. It’s got to stop. (Contains at least two good ways to fix this problem.)

Several years ago, we worked with a senior leadership team of a large, complex regional organization with dozens of locations and tens of thousands of employees.

The CEO came to us with a problem:

"We're doing everything we can to empower people. They just don't want to take responsibility."

The senior team met weekly and had done a great job describing their ways of working – they had a clear charter for not just the LT, but the way they wanted to meet, and how they wanted to interact with the org.

But even with a high level of intention, and the work ethic to back it up, they had a problem with team empowerment and engagement in the levels below the SLT.

We dug in further to see why they weren't getting what they wanted, because there's usually something else going on when you hear a quote like this.

After asking around, it was clear that there was something else going on. Examples:

- Despite explicit decision rights being given to an individual VP, when the time came to make a smart call about opening a new location, they were held up at the last second to wait for approval from another set of hidden stakeholders (that team lost the deal for the real estate as a result).

- Whenever it came time to make a decision, another additional committee appeared, needing to see the slides.

- When teams operated with transparency and shared their plans, other portions of the organization would raise concerns to leadership and slow their progress.

This was obviously not a situation where teams were shirking their given empowerment.

What was happening with the SLT?

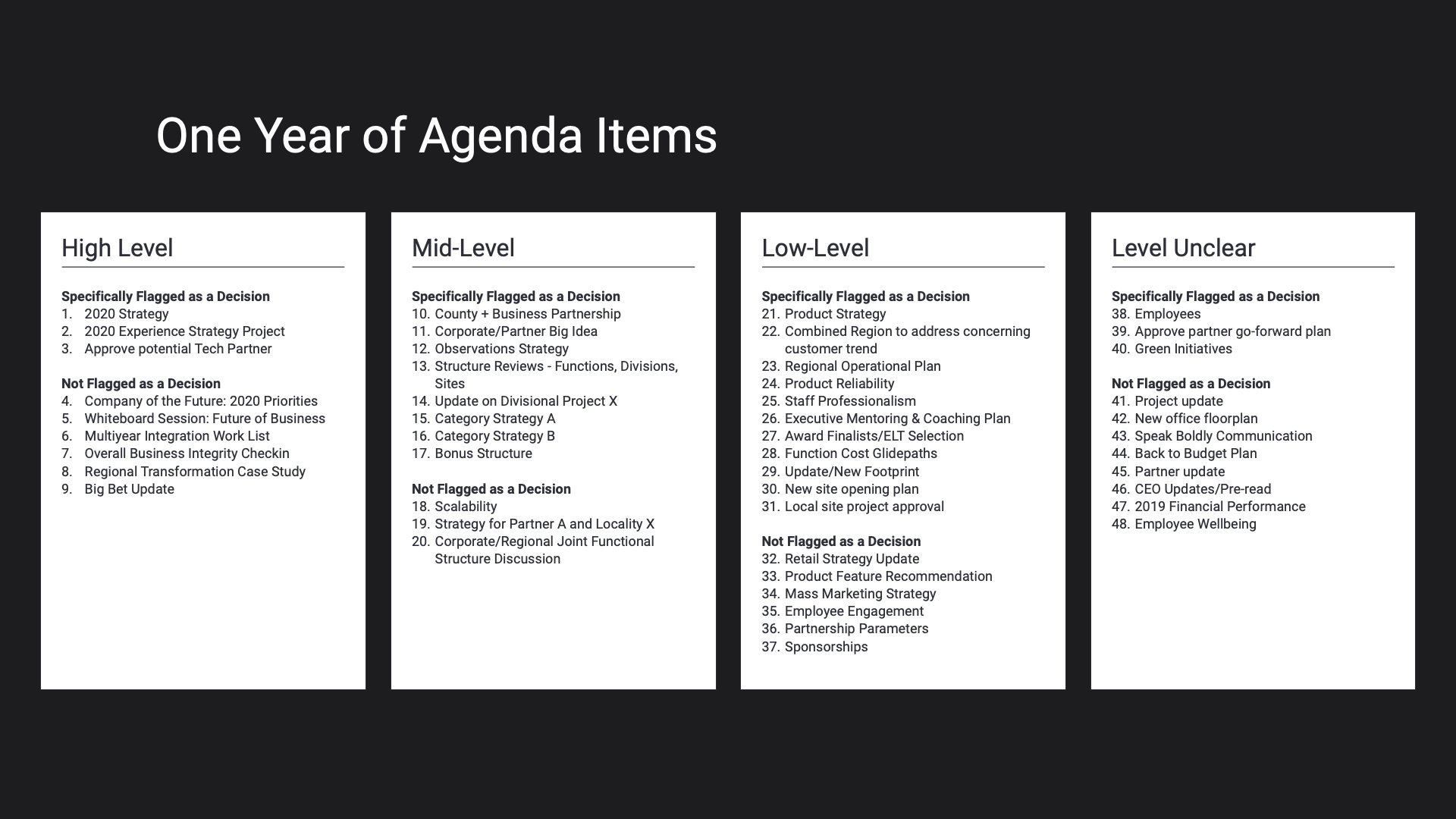

We asked the SLT for all their agendas from the past year, and this is what it yielded: 48 items, which we were able to sort quickly and play back to them. We popped these into a survey with a simple question for each decision: should this topic have made it to the SLT table, based on our charter?

SLT Charter

- Approve strategic people, program, facility, marketing, capital and budget plans

- Approval of all major budget items before they reach the holdco level

- Any ad-hoc strategic decisions related to innovation, communications and culture

In a few minutes we had our number: more than 70% of the agenda items shouldn't have made it into the room; they should have been decided at a lower level of the organization, faster, and with richer data.

This means that out of the 2,400 hours that this most senior team in the org met that year, 1,680 of those hours (or so) could have been spent on other decisions.

So what do you do about it?

Our first idea – giving the organization practices to make better decisions – was helpful but ultimately didn't solve the problem.

If we give the org scalable practices for making decisions, they'll get better every day

Hypothesis 1

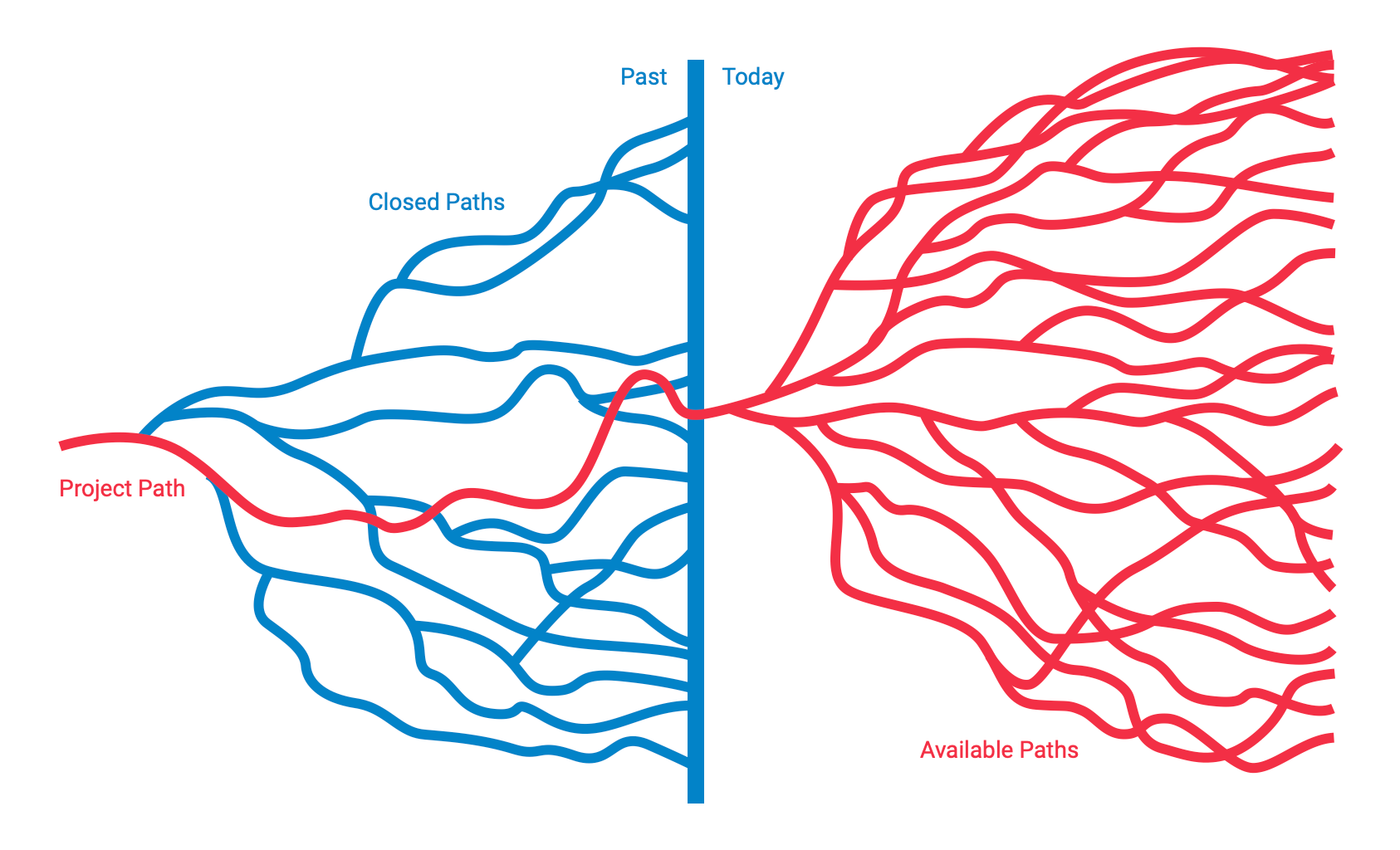

We tend to think in terms of decision-rights (RACIs, DICEs, RAPIDs) for problems like this. This is almost always the wrong idea, because project-level reality is more complicated than we think.

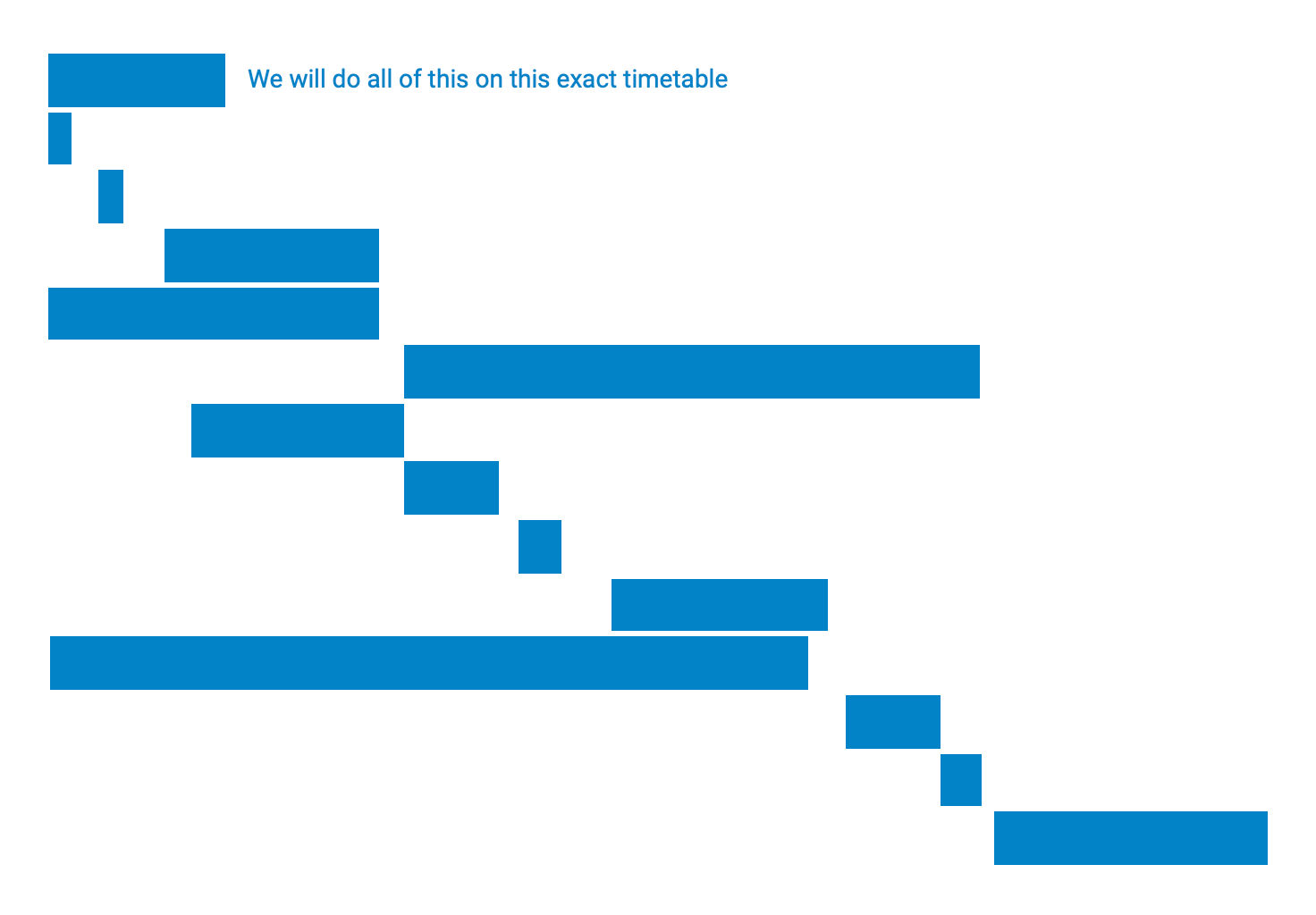

But projects only look like this on paper:

Big, chunky phases with pretty easy slicing of responsibility.

In reality, we know they look like this:

Try making a RACI for that, and you’ll end up spending all your time documenting, and not much time making actual progress; as you get further from the center or top of the organization, the decisions get smaller, more frequent, and harder to accurately describe.

A better idea is to give people better practices for making decisions.

In general, there are three things we’re trying to do here:

- Helping people notice what sort of decision they're facing.

- Helping people deciding how to decide.

- Helping people managing conflict between two good options.

All of these are under-described and under-practiced.

We offered some shared language, tooling, and guidebooks to help teams through this:

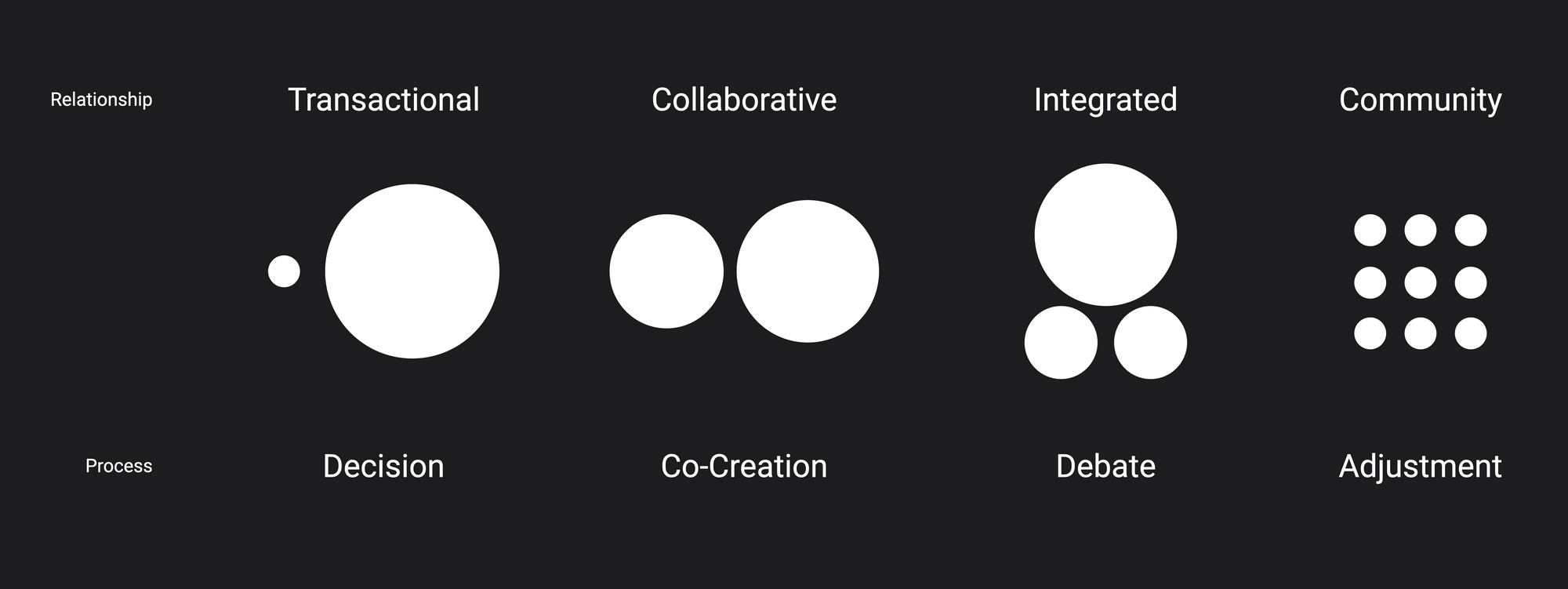

Each of these kinds of decisions is driven by the kind of relationship you want between different parts of the organization. This is adapted from work by Susan Finerty, Gregory Kesler and Amy Kates. Grab their books!

Transactional Relationships

To build and reinforce transactional relationships, we start with simple agreements based on clear decision rights. They are made by a single individual or team because their rights have already been granted, are implicit to their roles & responsibilities, and/or do not require outside approval.

- Who is involved: An individual who is empowered to make the decision based on their role, authority, as well as understanding of subject matter.

- Objection Handling: Decisions are made by one individual with express rights, so there isn’t really any room for objections.

- Examples: That situation above where a real-estate deal that didn't get dealt with quickly enough? That's a situation where a transactional relationship would have made more sense than a collaborative one.

Collaborative Relationships

Collaborative relationships are required when two parties who have overlapping interests and need to reach a shared decision. This means that even though there might be one party who is a clear owner, another has a significant stake in the outcome.

- Who is involved: One clear decision maker with another consulted individual that will be impacted, have impact on, or own responsibility for implementing the decision. Some governing body also needs to exist to decide who gets the golden vote (see below).

- Objection Handling: The best practice here is to give one party a pre-established "51%" golden vote. Leaders need to hold these parties accountable to work together towards a mutually agreeable outcome. For the sake of expediency, if there is a disagreement, the member with 51% will have the final say. In effect, this is "the boss" saying, "Don't escalate if you can't agree. Party A can break ties."

- Examples: LLCs with two members are excellent examples of this idea, where one member has the legal ability to break a tie, but both expect to work well together...and the business functions as a 50-50 partnership in all respects. In a matrix organization, either global or local role might be given the golden vote depending on whether the strategy demands consistency or innovation, respectively.

Integrated Relationships

Integrated relationships are required when members across different groups have to negotiate an outcome that impacts all of them, or where neither group can proceed if the other blocks their progress. When multiple groups need to be involved, uneven outcomes may require a superior to make the final call.

- Who/what is involved: The members who will be impacted and a designated superior. Templates and canvases for stage-gates will probably be a big part of this kind of relationship/decision-making process.

- Objection Handling: Just like above, but no golden vote exists. If consensus can not be reached, a superior breaks the tie.

- Examples: New product launches, where multiple different parties need to agree before proceeding.

Community Relationships

Community relationships are built on top of multiple teams that have a common interest and must reach consensus on decisions. In this situation, everyone needs to “sign off,” because everyone is impacted and invested in the outcome.

- Who is involved: Groups or individuals that are responsible for implementing the final decision, or who uniquely hold the information necessary to make the decision. For this kind of decision, group members need to be established upfront and limited to a reasonable number to prevent unnecessary cycles, with some individuals acting as representatives for different demographics/functions/departments/etc. That number is probably nine.

- Objection Handling: If an objection is brought up, the proposal must be amended until all parties involved can agree.

- Examples: Anything cutting across an entire population should probably be decided in this way. Changes to values, important policies, other governance, etc. That almost never happens, but it'd be cooler if it did.

We heard a lot of great feedback from teams on these ideas, but after a few weeks of trying them on, there still wasn't much change.

We needed something bigger.

The problem to fix is confusion about who gets to make which call

Hypothesis 2

What we found was that teams are escalating things that don't need escalating to avoid pain.

It's painful to find out there are 5 more committee meetings that need to see the slides. It's painful to get held up from making a good business decision – and to lose out on something important as a result. It's painful to hear heckles from the peanut gallery while you're being a good corporate citizen.

Instead, teams chuck it up to the SLT and let them hash it out.

Our strong hypothesis was that most of this was due to confusion on who could make what call, rather than malicious compliance.

There are a few ways to sort out decision-making among senior leaders. All of them result in naming winners and losers: some people take over the decisions that others were making before. As a result of this work, the organization is wins some new effectiveness, and some of the individuals are losing stature. So even though this is a zero-sum game between the business and its people, the alternative isn’t one we can accept.

The answer here is to go slow, be methodical, and help people deal with the losses.

Here's what we recommended.

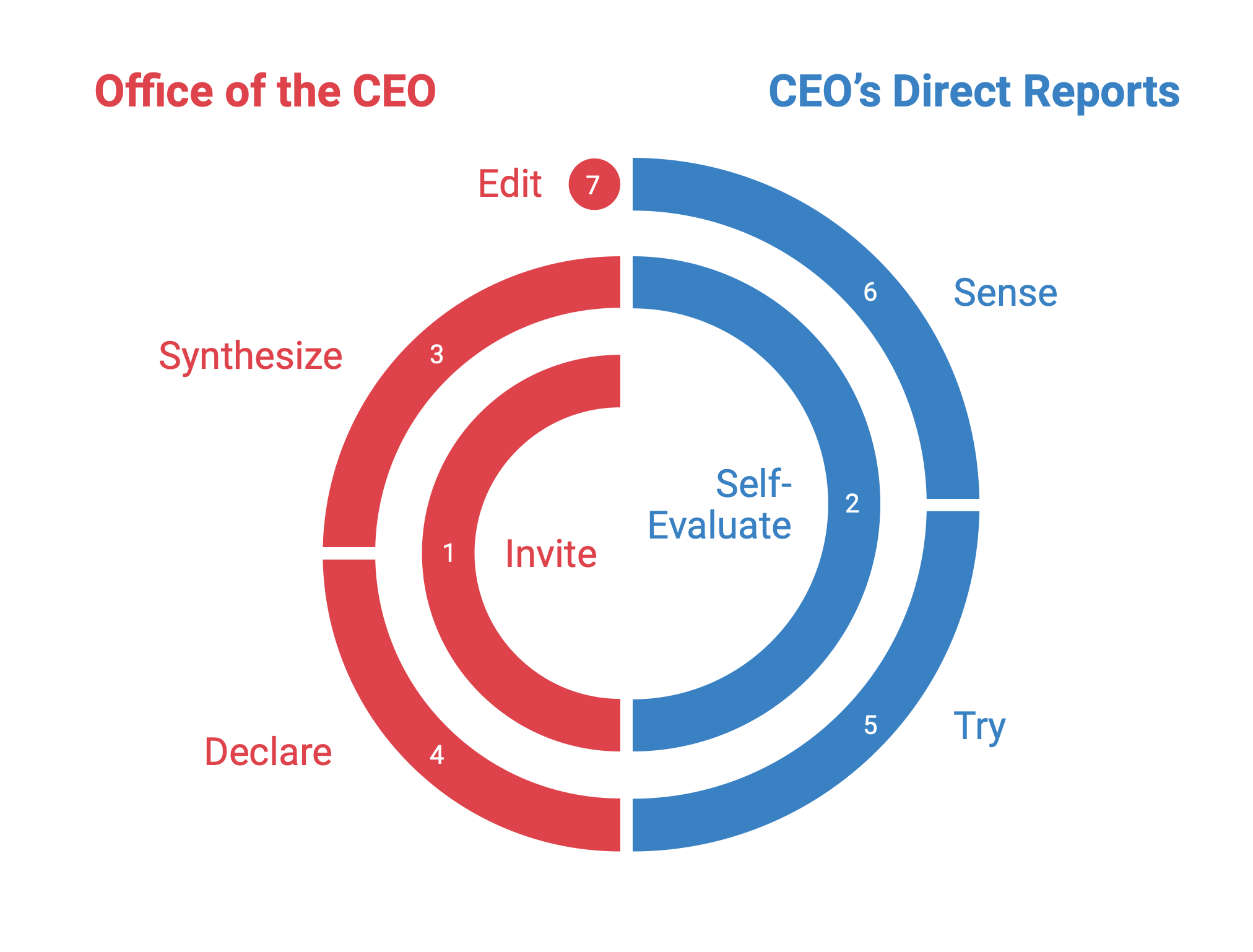

There are two cohorts to work with here: first, the office of the CEO, which consisted of the CEO himself, his Chief of Staff, and Executive Assistant; second, the group of eight direct reports, which were a mix of divisional and functional leaders. We settled on a call-and-response pattern between the two groups:

- Invite to change, with a clear explanation of what could change, the process being used, and how to participate.

- Self-evaluate: We asked each direct report to individually consider two prompts. “What do I own?” and “What do I think I should own?” We gave them a template to help structure their response, but if you are doing something similar, a simple spreadsheet would do.

- Synthesize: Gather up all the inputs from each direct report, and work to understand overlaps and gaps.

- Declare: Decide which senior leader should own which thing, and workshop those decisions with the direct reports. This stage is deeply political and precarious, as there will always be winners and losers. It’s important to allocate time and attention here. Be ready to reiterate that the old system wasn’t working, and keep the corporate strategy near at hand to help give legitimacy to transfers of power.

- Try: Give the new operating system a go for a reasonable amount of time.

- Sense: Notice where breakdowns and reversions to habit happen.

- Edit: Using what the directs have noticed, edit the governance. (Keep doing 5, 6, and 7 … more or less forever.)

Wrapping Up

This stuff requires constant attention, and the only ways I’ve seen firms stick to consistent, market-leading levels of “decision quality” is by making it part of what it means to be a member of the group.

At Amazon, if you don’t operate according to the Leadership Principles (LPs), you’ll quickly find your way out of a job.

Here’s their LP covering this topic:

Have Backbone; Disagree and Commit. Leaders are obligated to respectfully challenge decisions when they disagree, even when doing so is uncomfortable or exhausting. Leaders have conviction and are tenacious. They do not compromise for the sake of social cohesion. Once a decision is determined, they commit wholly.

At NeXT (and I assume this is something he carried forward to Apple) Steve Jobs brought passionate commitment not just to good choices, but to the governance framework that would consistently produce those good choices.

For anyone leading a team – global LTs and working teams alike – this ought to occupy something like 30% of your attention.

Anyway.

Around a year later, I caught up with a member of the LT from the story above and their reflection was that the process was painful but necessary: they used their improved governance to respond more effectively to COVID-19. Which is, I guess, what all of this stuff is about. Why spend a bunch of time on decision-rights? Why go through painful redistribution of authority?

Because all those thousands of hours of bad escalations compound something like 10-100x across the org. There aren’t a ton of chances for any org to instantly multiply their productivity without spending any more money. This is one of them.

Comments