The New Model for Scaling a Company

Three old technologies (rule of law, market forces, and transparency) can help us move toward seven universal performance criteria for organizations: purpose; fitness; vitality; fairness; power; connection; safety.

Here's a talk I did in 2015 at Percolate's Transition conference. YouTube ⤴︎

This is roughly what I was trying to say:

The dominant narrative — the story we all believe to be true — is that when companies get big, they get bad. We wonder this aloud to our colleagues on Slack — “how big can we get before we get bad?” — and we see evidence of this narrative everywhere.

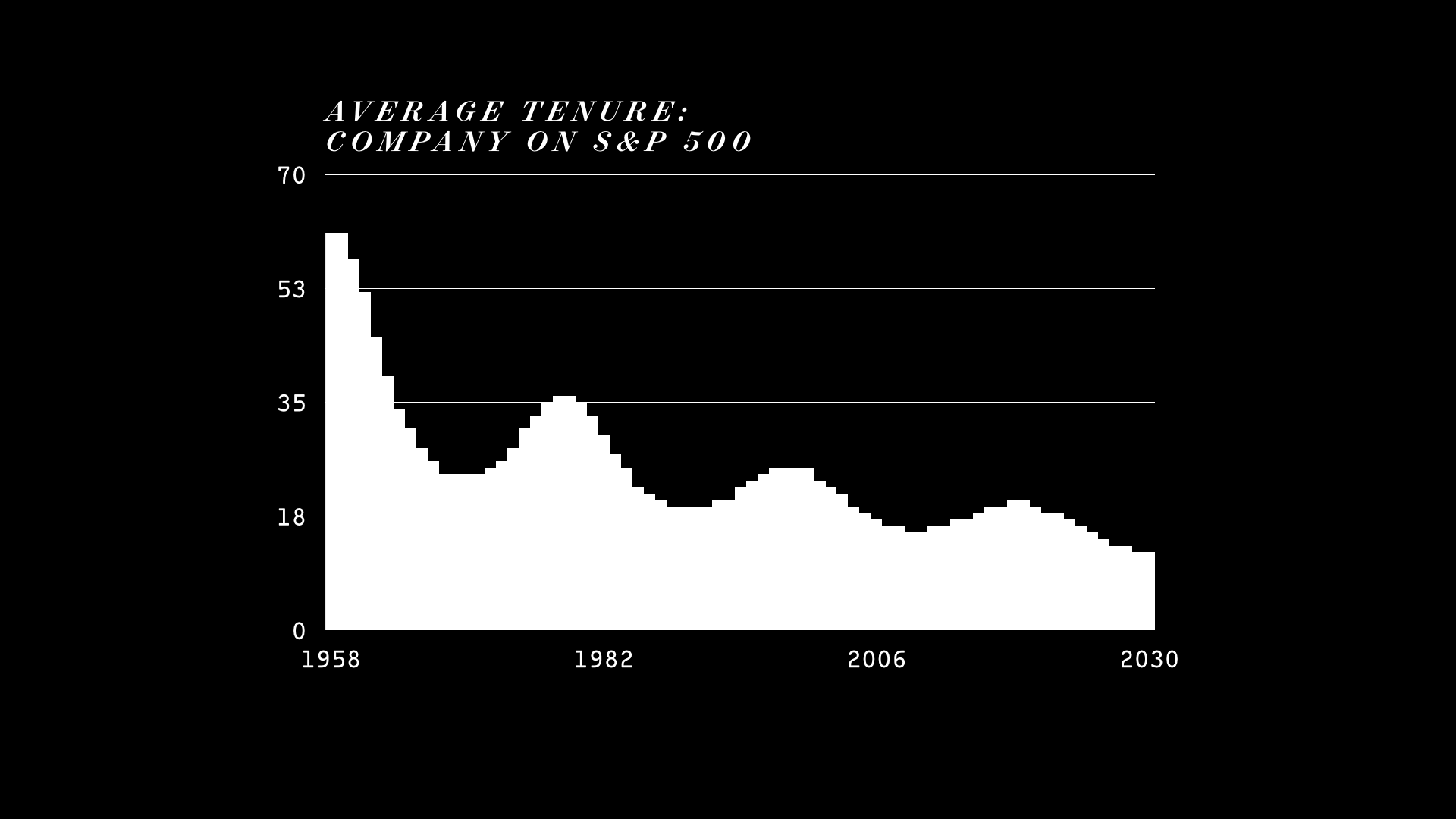

We see it when we look at the tenure of the companies listed on the S&P 500,1 down now to 18 years.

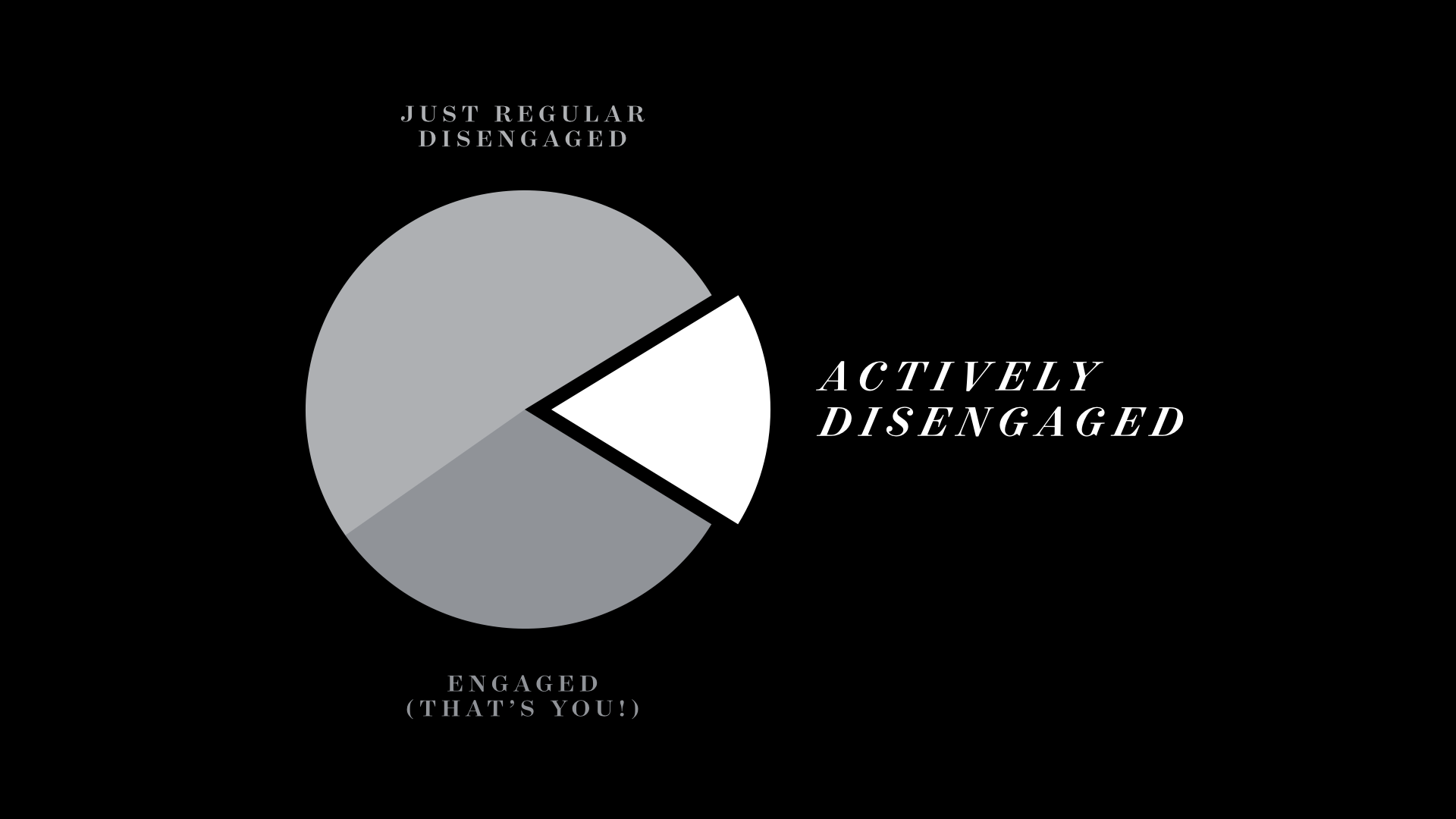

We see it when we look at engagement at work. In the United States, fully 17% of workers are actively working against their employers and colleagues, and half are just plain checked-out.

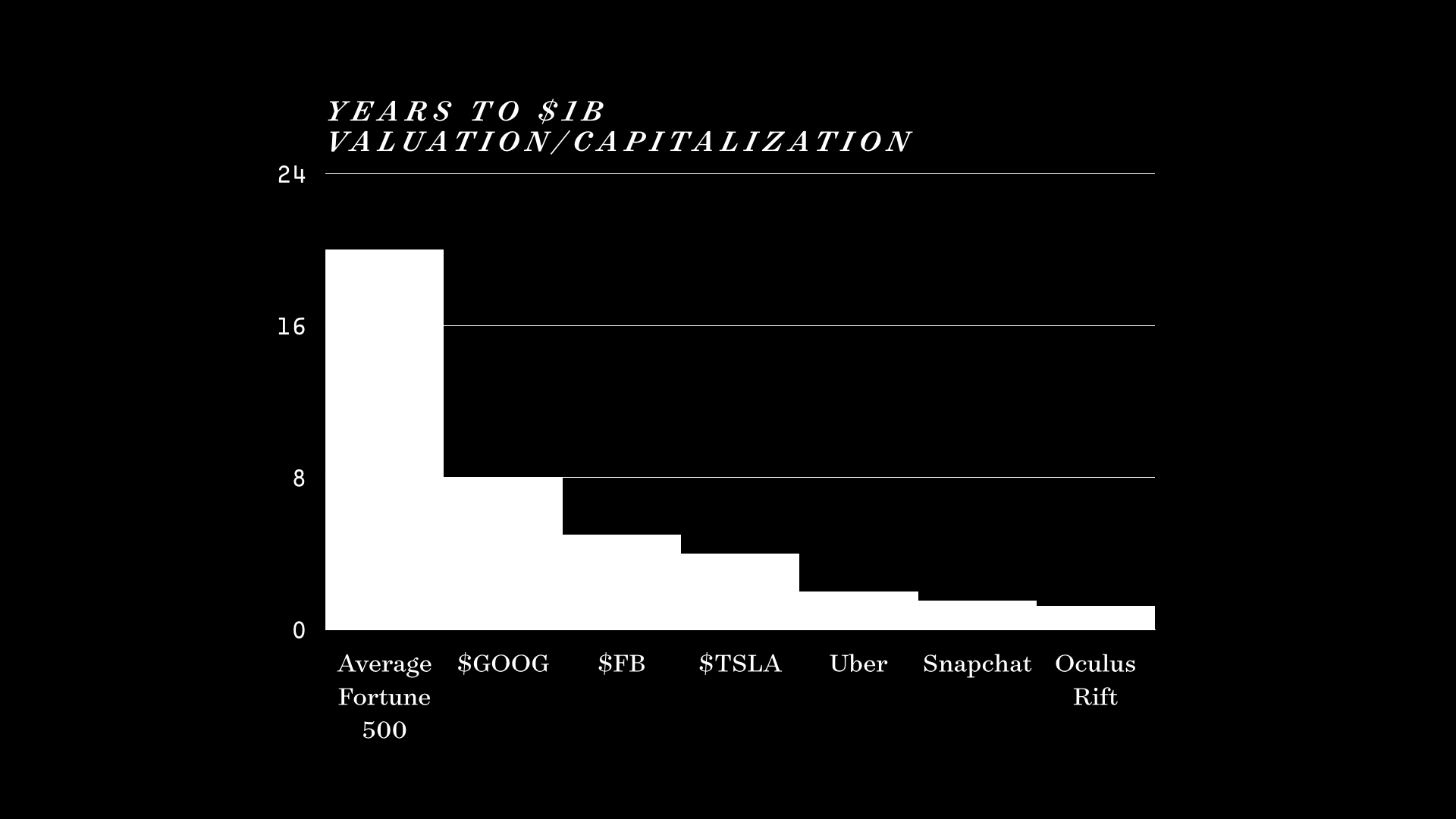

We see it when we look at what tiny firms are able to do, how quickly they’re able to grow, how much good they do in the world. Contrast what Tesla’s 12,000 employees are able to do with what Volkswagen’s near 600,000 have done. People can do amazing things together, but they can also perpetrate deeply unnerving evil.

So it’s no wonder that — unless we’re incentivized to believe differently — we’re afraid of scale. The way we grow is by capturing new territory through extensions of our line, through acquisitions, through campaigns waged against competition and consumer alike. It’s all so medieval.

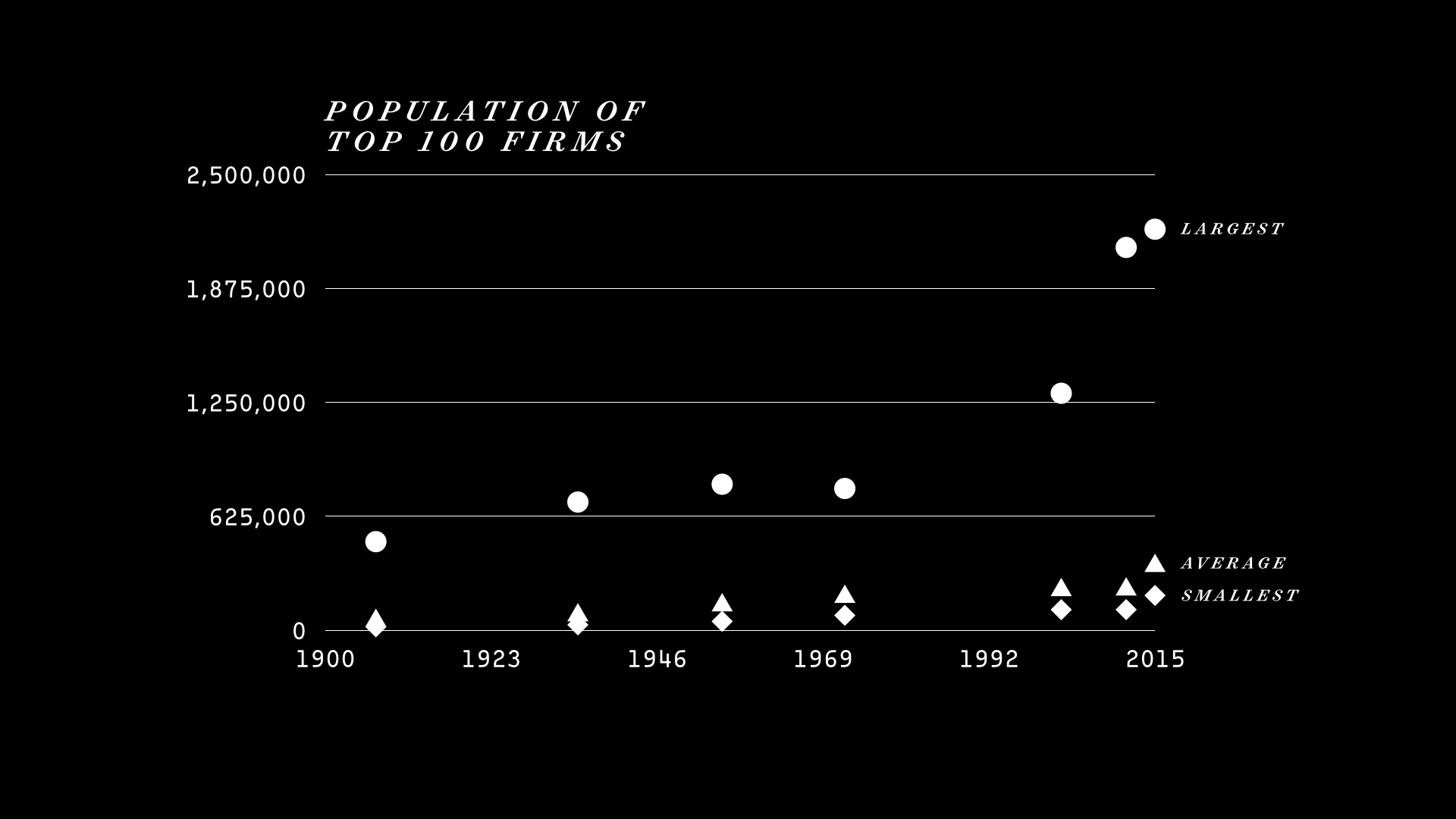

And yet! Firms are growing. The average population of a top 100 firm is now 350,000 people. In the 1970s it was half that.

With all the badness big firms create, why are they growing? Because it’s fun? Because it feeds our egos?

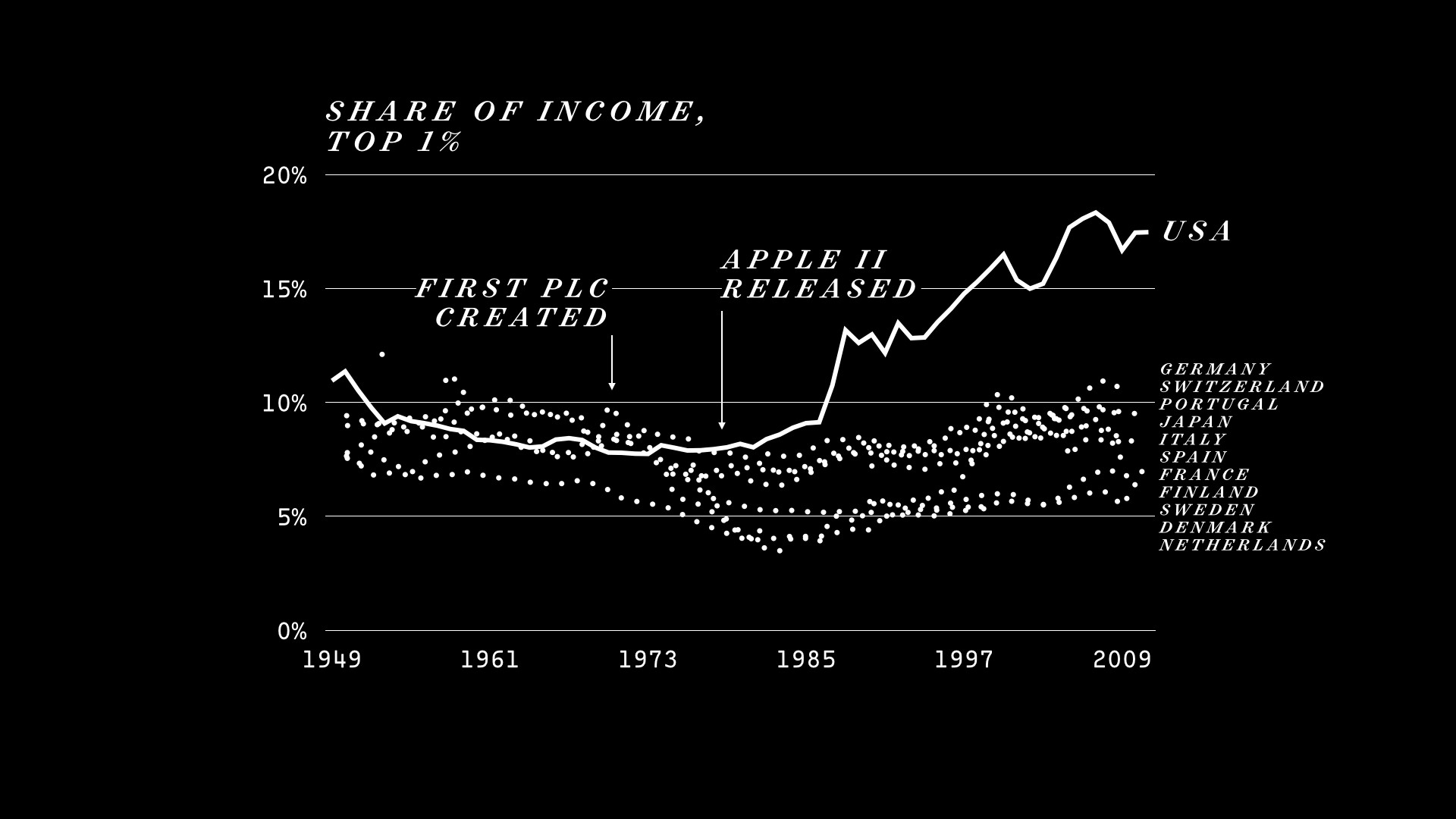

Because size does have a huge benefit, and software has made the financial advantages of scale even more powerful.2 This chart should make clear that we can indeed choose the kind of world we live in – and though our organizational choices we’ve decided on a world few of us actually want to inhabit.

Could there be another option? One where we get better as we get bigger? We’ve seen today that some systems get better with scale, that outcomes in parts of the world are improving, that we can harness digital technology for the good of all.

I’ve spent the past year studying those that study these kinds of human systems, both organizationally and in lateral fields like cities and governments. All of these theorists and practitioners — and the teams of people that allow their work to grow and spread — have identified discrete sets of principles in their work.

We talk a lot about wanting organizations to improve. We talk little about exactly what kind of change we want. I gathered these principles3 and studied them to understand what we want to happen when humans come together to work – an activity that we’re increasingly doing for free or at least on our own terms.

What I found was a set of universal Performance Criteria — an idea I took from Kevin Lynch — that held all of these principles together. We can use them to judge all organizations; the output is as applicable for Walmart as WhatsApp.

- Purpose: The work we do here is important to us and to our customers; We gather according to a clear purpose

- Fitness: Those who consume our product believe in its quality; We achieve impressive things together; We make sense in the world

- Vitality: Not just fun, but vital, life-giving; Our lives improve as a result of our membership in the organization; We get energy from our work; Our culture is contagious

- Fairness: We make decisions taking everyone’s needs and advice into account; There is a strong sense of justice; Everyone in the organization has the same basic rights

- Power: More, and more forms of power for all; Power is spread throughout the organization, not just kept in the hands of a few4

- Connection: Boundaries between teams are permeable; We don’t see our users as outsiders; We offer signals generously so others can learn from us

- Safety: People stay in the organization by choice; I won’t be let go for personal reasons; It’s easy to do good work; We have what we need to succeed

Let’s agree for a moment that this is what we’re going to work toward, that we’re all going to try to build organizations that achieve these things. How should we go about doing it?

We should apply lessons from history – old technologies – to our working lives, no matter where we work, no matter what position we hold, no matter what amount of power we have over the direction of the firms that pay us for our labor.5

We must replace Tyranny with Rule of Law.

A concession: large firms mostly have good corporate governance. They also mostly have organizational governance that prescribes who can make what decision and in what way. In general, these tools actually stand in the way of a true application of the Rule of Law, rather than supporting its sustainable growth.

Here’s why: “governance” typically comes in the form of a standing meeting where a group of subordinates recommend a decision to one or more senior officials, who either say yes, no, or go do more digging. This is tyranny, or at the very least, it’s a feudal approach to organizing human work. The alternative approach is one where we don’t let a single person or a small group make arbitrary decisions that impact a whole, but instead we vest authority in a system.

This is very hard to achieve in practice.6 1. Because what do we do with all of the history we have of doing it the other way and 2. If the bosses don’t get to decide everything, what do they do? and 3. What incentive, then, will people have to move up? We need new systems to hold this change, to be sure, but that shouldn’t stop us from making progress.

A quick pause for a new mental tool: a sort of behavioral strategy, a way of prioritizing things in life, where you hold yourself to one good thing EVEN OVER another good thing. Choosing between a bad thing and a good thing is far too easy. For each of these old technologies, I’ll offer a statement that you can use in your day-to-day to make these huge changes WORK in practice.

- Elect even over Select: Starting within a team, instead of deciding who does what, use a process to elect those role-fillers. It’s an extra step, to be sure, but it’s one that rewards capability and teamwork.

- Process even over Decide: We have traditionally valued individuals who are decisive, and those who are frequently correct. And our structures are designed for this, designed for one person to make the call. We can be more inclusive, we can incorporate more data, by instead using a trusted process for making decisions, where we *process* data through a pattern versus feeding it to an individual for their yea or nay.

We must replace Central Planning with Market Forces.

Large organizations are led by very smart, very successful, very capable people. In general they are trying to do good in the world. The problems they face are just too hard — too complex to be solved by even a small group of extremely focused experts. On the face of it, we know this to be true, that planning centrally for what will happen 5 years from now in a perfectly connected and unpredictable global economy is just too difficult. And yet we do it anyway. We should instead organize for and build culture to support market forces within the organization, replacing Alfred Chandler’s visible hand with a more market-like condition.

- Describe even over Prescribe: Everywhere I look in big organizations, I see prescription. Leaders set targets, define budgets, interrogate project plans.7 Instead we should focus on description. Describe where we’re going as a team. Describe what kinds of things would indicate success. Describe what a user’s needs are, leaving the tech prescription out of the picture. Eliminate the dependency on industrial-era motivation tactics and watch your team surprise you.

- Focus even over Help: We’re taught to be helpful, to be team players, to do whatever is necessary to help the organization succeed. To bring Market Forces into our organization, we need to start thinking of each team as its own company, with its own measures of success, its own funding sources, and all of its output considered a product “shipped” to customers. Helping other teams is good, but focusing on improving our product as a team gives us the chance to move and change faster than any centrally planned organization ever could.

We must replace Opacity with Transparency.

This is different than eliminating personal privacy. Instead, we must find places where we are hiding information from one another, intentionally or not — inside the ever-more-vague boundaries of the organization — and make that information freely accessible to all. We use opacity to protect ourselves from scrutiny and to ensure that meddling outsiders don’t derail the progress of our teams, to be sure, but sometimes we default to opaque because we don’t have good social and digital systems to put work in public.

- Open even over Closed: Start with the idea that everything should be in public, and work backward from there. What absolutely needs to be kept private? What would put us out of business — actually — if it leaked? Presume that everything else can be accessed. In doing this, you’ll make make yourself and your team more like software — declaring to the world how you work, what inputs you need and what your output is.

- Pull even over Receive: We have commercially available, frequently free systems for efficient, zero-cost knowledge transfer. They very rarely exist within large organizations. Set up software systems that allow people to GET the knowledge they need, rather than have it pushed to them. Give them agency to do so.8

This is all part of a new model, a new way of working that has always been a good idea, but a good idea before its time. We didn’t have the tools available to us to make these old, social technologies practical in a fast-moving corporate world that does need to generate capital to sustain life. But now we do. Now we have software that makes it possible for everyone in the organization to work on its structure, its culture, its process and its use of resources. We can distribute authority to teams and trust them to create. We can set the organization and its people free to do great work.

This is a permanent shift in our way of working, one driven by technological change. We’ve seen this before — and economists like Carlota Perez have given us the tools to understand that we’re now entering the distribution phase of this shift, and the confidence that the big firms of this time, if they are able to adopt this new way of working and organizing, can survive through to the next one. But that’s a big if.

While I’ve made this my life’s work, making this change happen is your job. In fact, it’s everyone’s job. Teams know what changes are most needed for their context — take the license to make work better and do more important work.

Commit to the change. Commit to measuring progress against a new set of performance criteria. Commit to building a better world.

- Important: this is different than firm mortality.

- Successful application of the tools of our day can have huge impacts on human productivity, but only a few firms have figured out how to actually bring this advantage to life.

- You can find a comprehensive list of these principles here

- Senior leaders have so much power that they can’t possibly “spend” enough of it on any given day to achieve the purposes of the organization

- To be clear about these technologies and their impact: wars have been fought over them. Actual guns-and-bombs wars. These are no joke!

- “In establishing the rule of law, the first five centuries are always the hardest.” – Gordon Brown. LOL good luck!

- Larry Page plan quote?

- If you’re a leader, know what KIND of work you’re creating whenever your direct reports present a deck to you – it’s not the important work that people came to your organization to do, it’s busywork to support a feudal decision-making process. Instead, help your team work in public by sponsoring open systems that allow you to SEE work being built real-time and PARTICIPATE in its creation – making your team sharper and helping the world become a better place. Also, dashboards. Set them up. Use them instead of PowerPoint. PLEASE.

Comments