The Founding Flaw of Matrix Organizing

Last year I was on a podcast with my friends at Zappi, and we got to talking about matrix orgs – there's an old bug inside the system, and it'll never go away.

If you've already listened to this podcast, that's awesome! There's a lot more below that you might be interested in, though – so keep reading.

It's become commonplace to call out scaled, industrial organizations for using an operational model designed 100 years ago.

I've said that! I believed this for a long time. But it's not true.

They're actually using an operating model designed 65 years ago, and it's a really phenomenal piece of social technology.

Quick trip back in time?

This is generally accepted to be the world's first org chart:

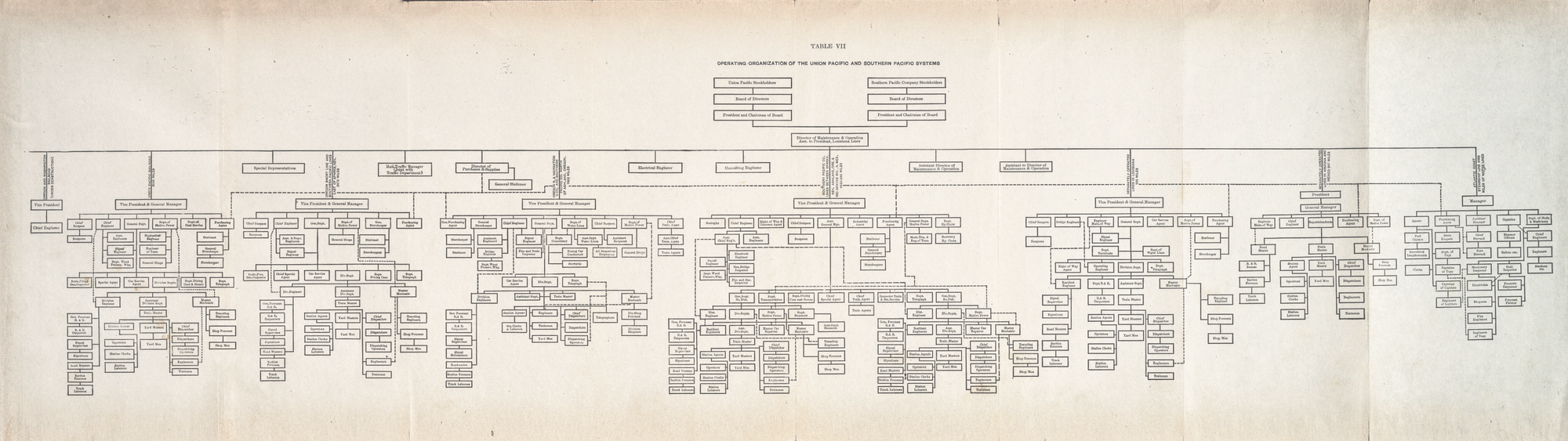

This style came along in the early 1910s:

Org charts like this get a lot of hate, but they’re remarkably effective, provided you can predict the future. And the early, big industrials weren’t just predicting the future, they were creating it.

The entrepreneurs at the top decide what to go do.

Plans cascade down from the top.

With enough capital and human suffering – markets get made.

This remained more or less unchanged until the space race forced (or enabled) a new operating model.

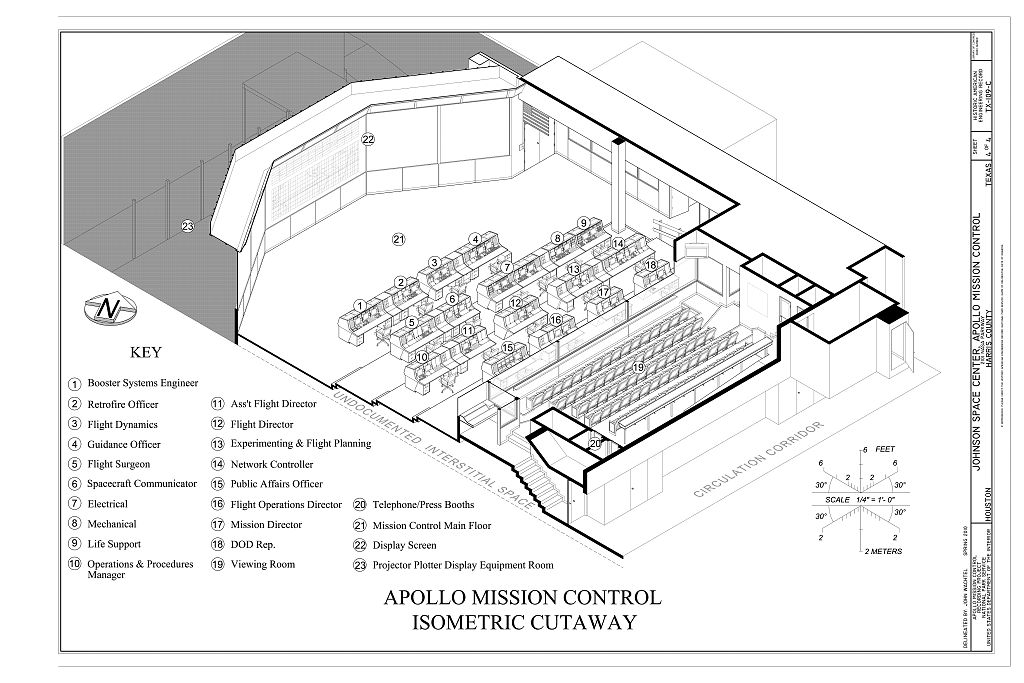

Getting people on the moon was a monumental effort, with hundreds of subcontractors working together toward a massive goal. This went way beyond building things to spec and hoping it works out – lives and national reputation were on the line. And it worked pretty well!

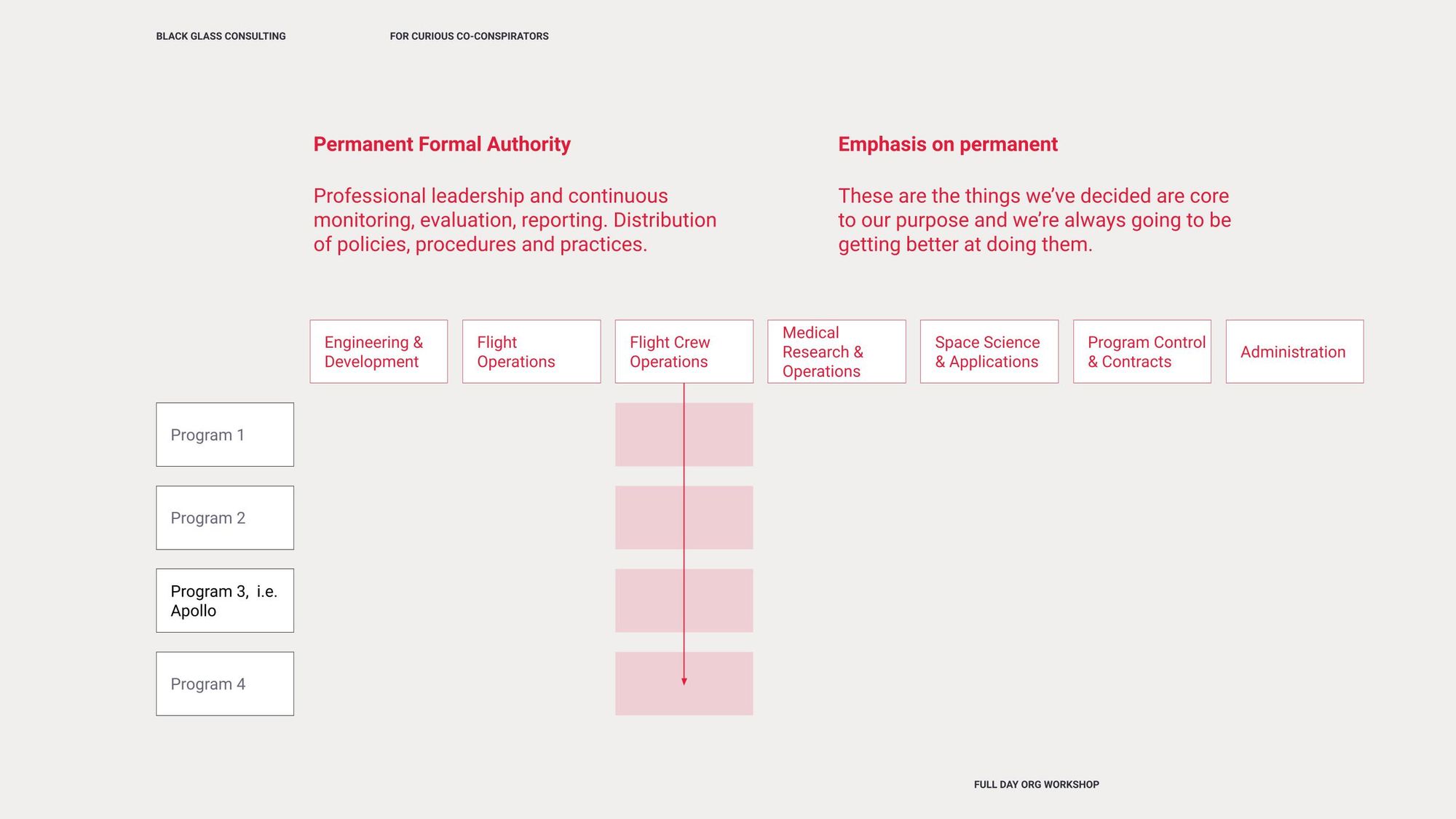

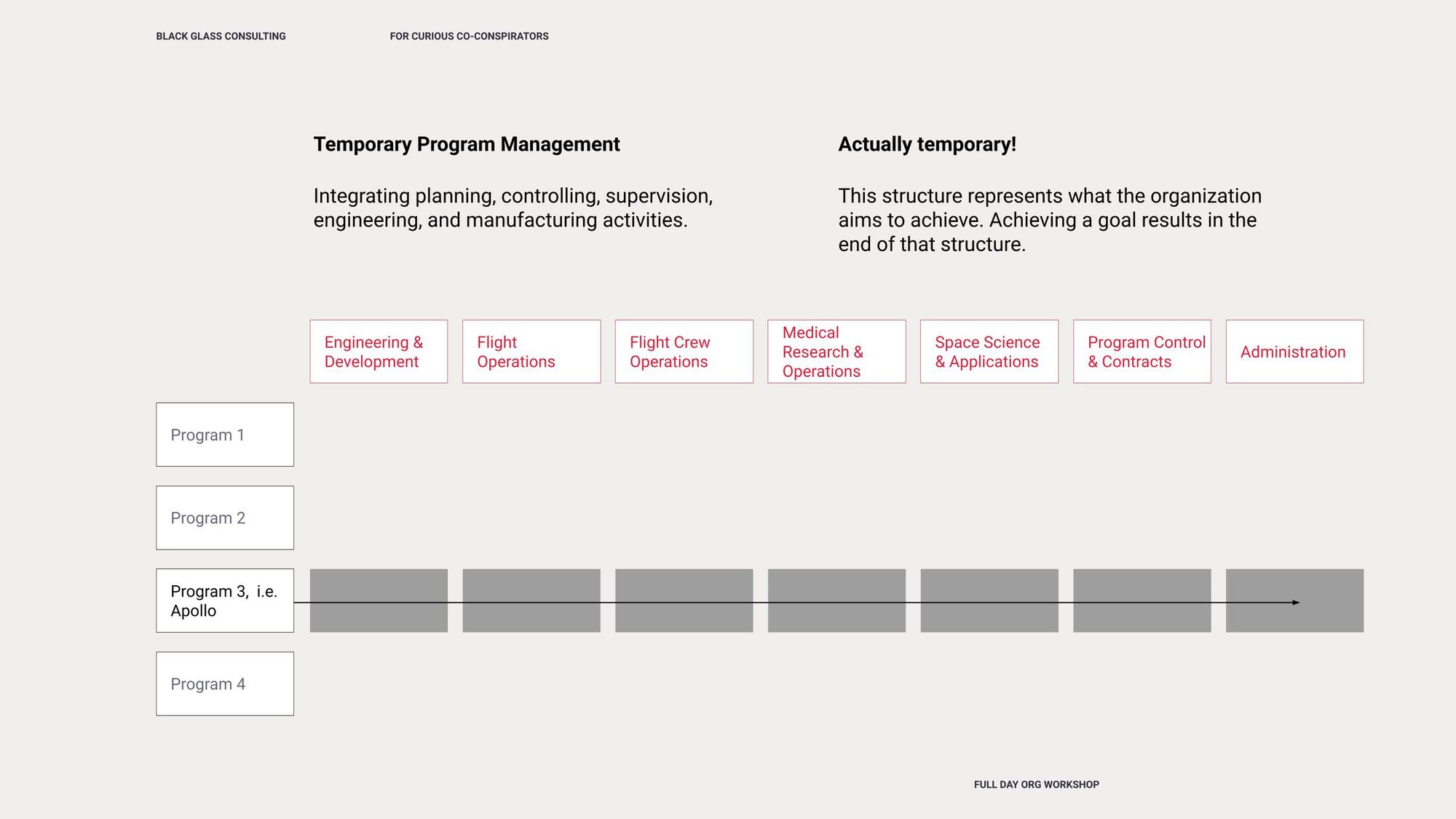

Some organizational features that went beyond line-and-staff:

Formal authority rested with what we would currently think of as "functions." These are things that set the space program apart from everyone else, and are core to their purpose. The only things that maybe feel generic in the structure are things like Admin and Engineering – all the other buckets are real differentiators.

Program management was assumed to be temporary. Achieving the goal of the program meant that its structure would go away. Can you imagine this in today's corporate environment? I'm sure that would be energizing.

And then there's decision-making.

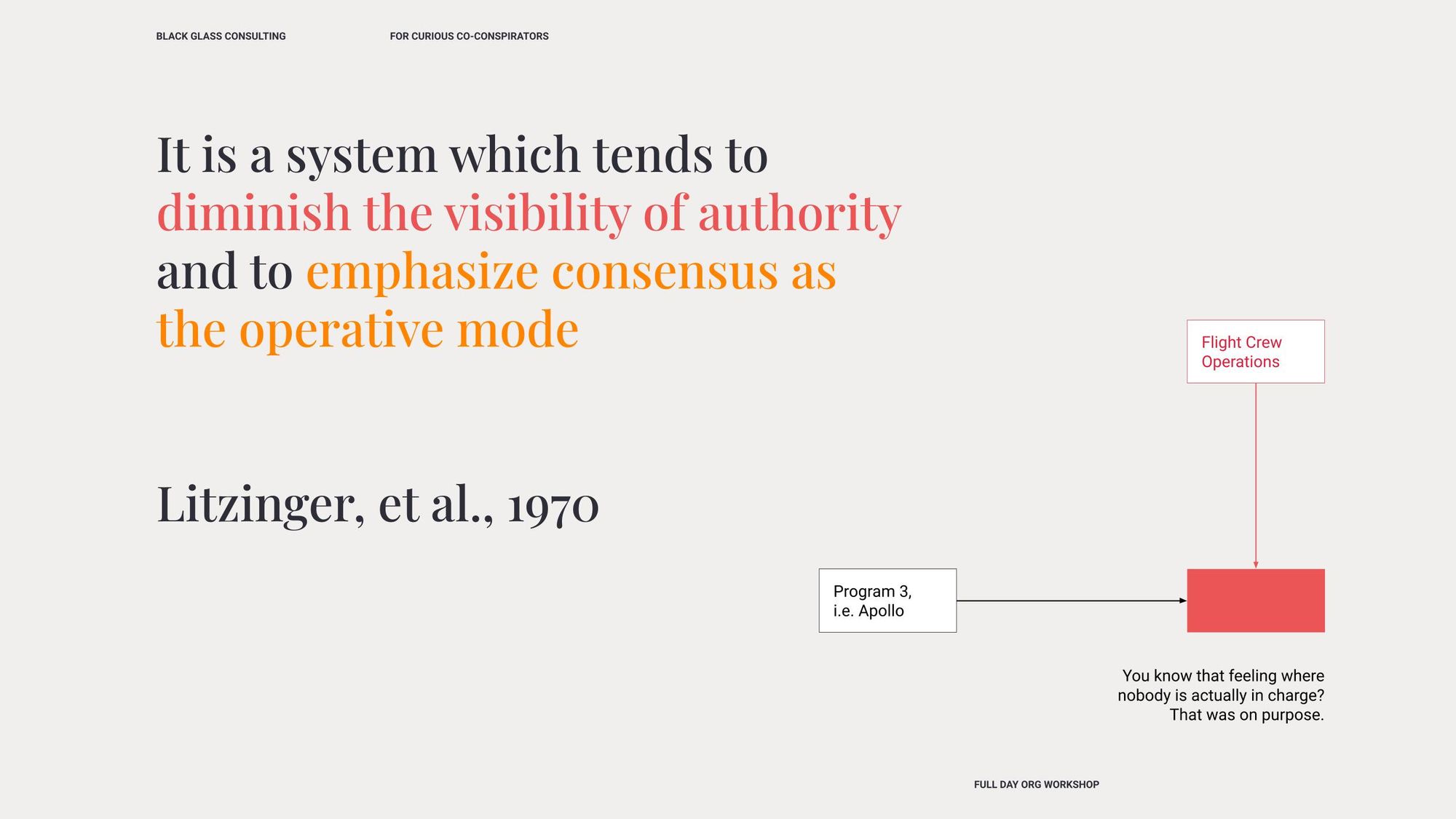

A key part of matrix management as exemplified at [the Manned Spacecraft Center, or MSC, in Houston] is the presence of elements with the power of precise decision, able to freeze the dialogue of decision making at ad hoc points. In place of hierarchy and the pressure to conform to directives from the top, matrix management MSC style, tries to substitute operating unit drive for expression within a climate of mutual respect united around fundamentals. Litzinger, et al. 1970

Basically, everyone in the matrix was expressly and culturally empowered to say "stop" at any moment. (Like an Andon cord.)

It's amusing to me that this kind of consensus is kindof a big part of space movies. Consider the sequences inside "Mission Control" in Apollos 11 and 13, and the debates between different contractors in The Martian.

And this is a documented, intentional thing. This is the "founding flaw," if you were waiting for it:

Diminish the visibility of authority.

Emphasize consensus as the operative mode.

Fine. But you're probably not launching rockets. And you probably don't have a mission as consequential as, say, the Space Race. So getting this way of working to work for you – where anyone can stop progress at any time, for any reason – without major integration risk and massive transformational purpose is gonna be pretty tough.

The end result

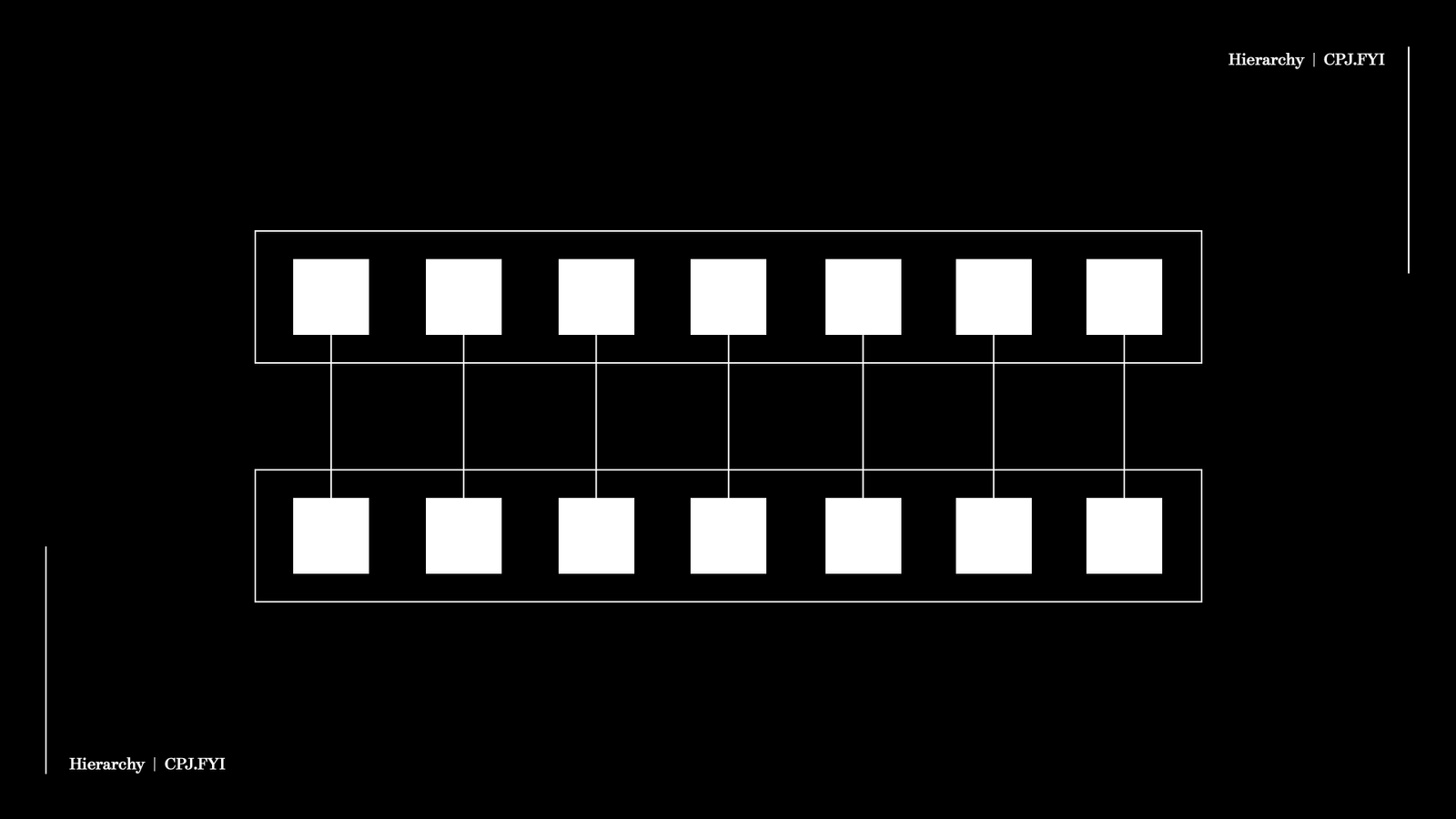

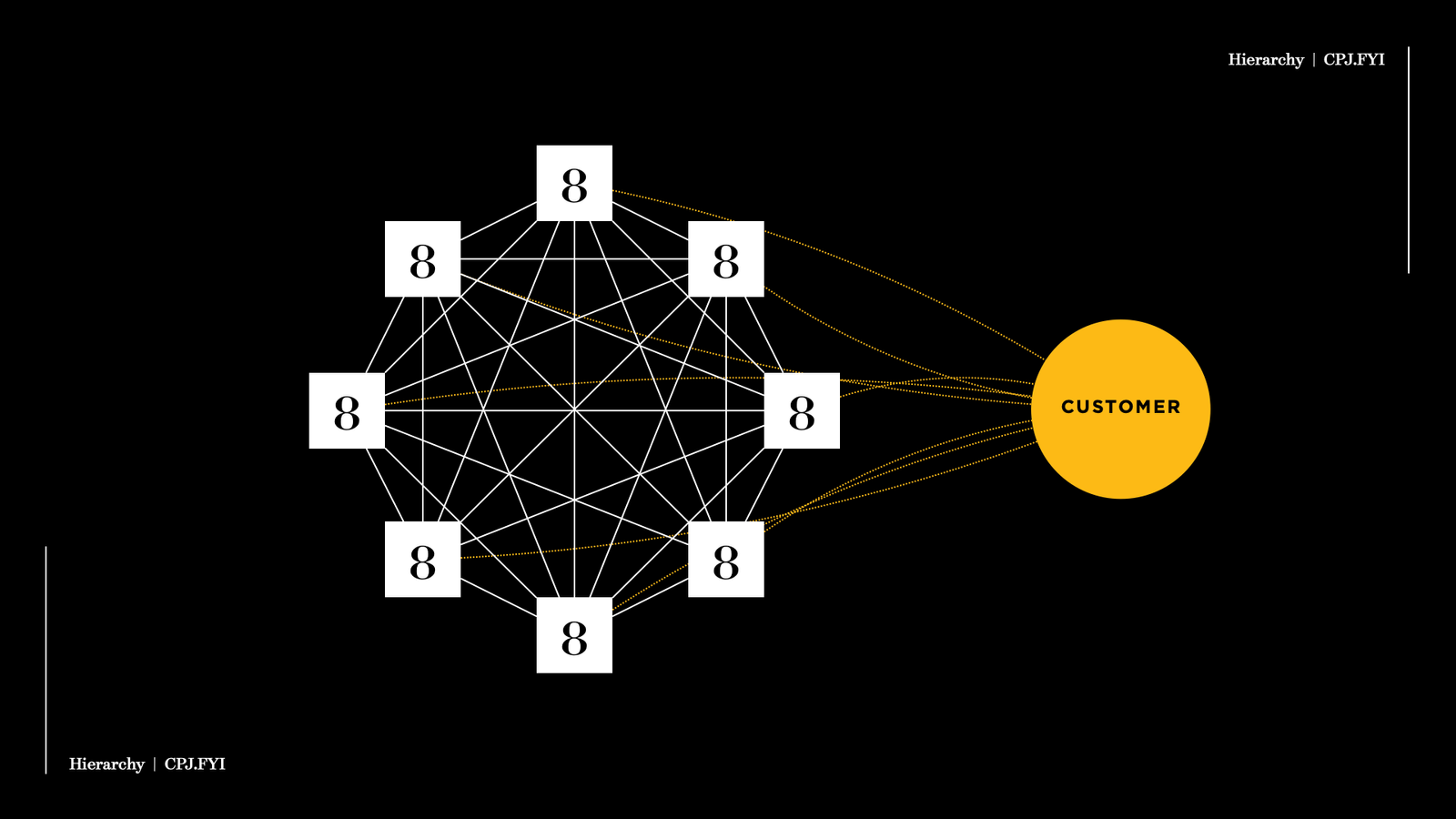

So you end up with this:

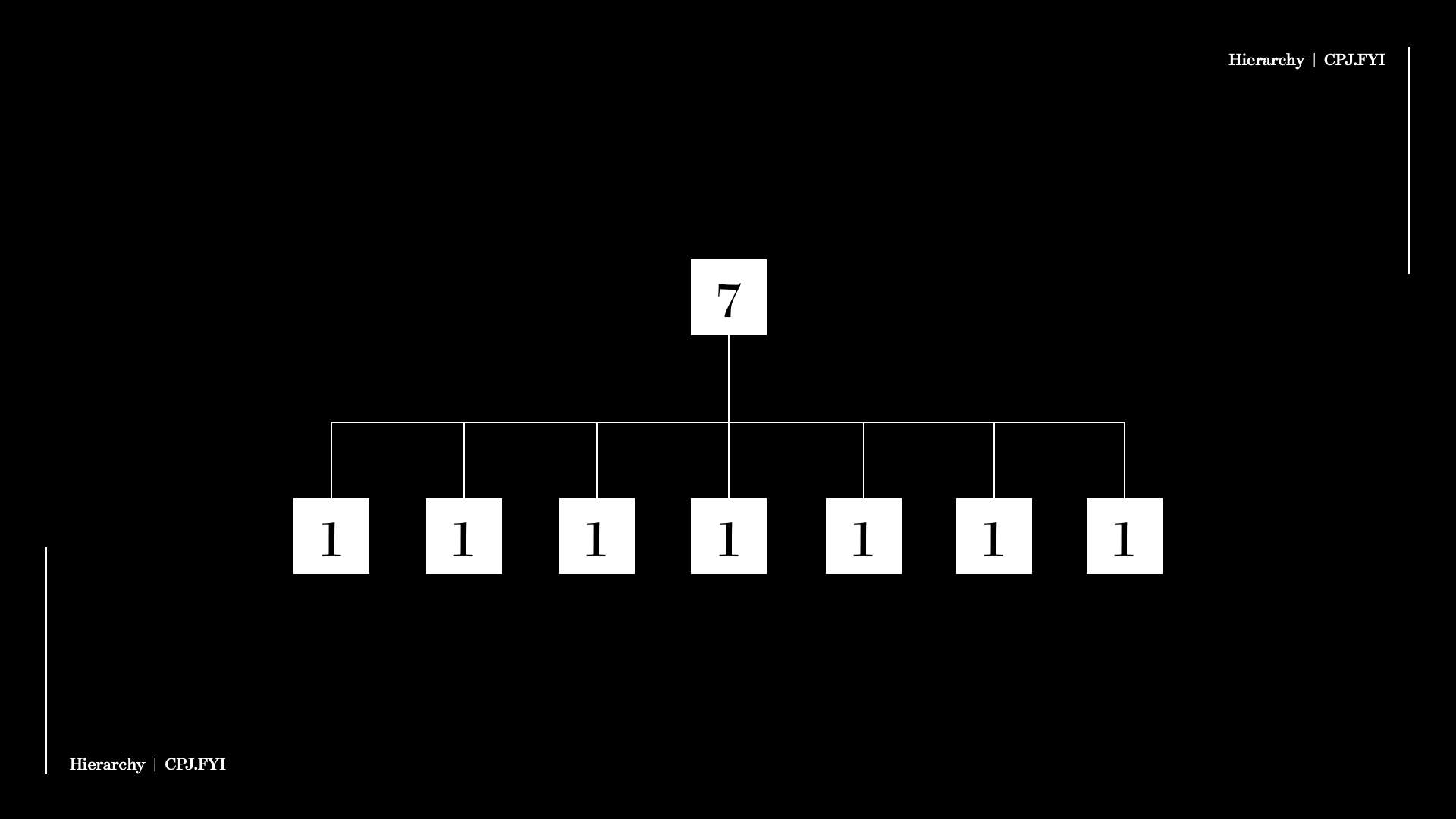

Not this:

"Fit this into a hole made for this, using only that."

I doubt that anyone has eight bosses, but it can feel like that on a matrixed team. When a team is made up of multiple different disciplines, and each of those disciplines has their own boss, and each one of those bosses has a different agenda and set of incentives, then it's possible that any of the people in the top box can stop the forward motion of any of the people in the bottom box.

A much better solution is to put people on an actual team, with an actual customer, and a clear commercial mission. Oh, and clear boundaries for what's allowed and what's not.

Comments