Why use this?

Strategic Compression is a way to improve the usability of strategic thought. Most of this kind of thinking is created and delivered to an organization in robust, sometimes extreme detail, which increases its momentary quality – it's very accurate given the givens, in the instant that it is created – but difficult to use and adjust with no data. This may be useful for situations that are resource-intensive, but if your business, project, function, division or team are facing high uncertainty, a more adaptable approach is required.

Use Strategic Compression...

- When you want to give people simple freedom within a framework

- When you want to enable a team to take action

- When you want to establish heuristics in advance of encountering a situation

- When you want to make prioritization judgment calls easily portable throughout an org

What is Strategic Compression?

The art of simplifying strategy into the most useful, editable, atomic version of itself, using some form of compression. This guide covers two compression styles:

- Articulating the strategic choice being made in the format of [good thing A] even over [good thing B]

- Articulating upsides, downsides, and actions associated with the two opposing "good things" you'll prioritize

Style 1: Good Thing A over Good Thing B

If you're looking for a simple – but quite difficult – method for capturing your strategic thinking, try expressing it in terms of one good thing that you're selecting, even over another equally good, valuable thing. You're probably thinking, "this sounds super easy!" but folks screw it up their first few (hundred?) times they try. This gets much, much easier with practice, though, and there are two pitfalls to avoid:

Big Error Number One: Good Thing Even Over Bad Thing

"Run profitably even over Go out of business"

This might be an indication that there are some big problems in the business that are worth solving, but these things don't tend to represent high-quality strategic choices between two equally valuable paths. Think of it this way: you're trying to identify something really, really valuble that you're going to actively decide NOT to pursue over the next while. And perhaps use those "bad things" that you've generated as a source of inspiration for process optimization, automation, or waste-elimination.

Big Error Number Two: Wordy/Boring

"Flawlessly execute our three big bets (launching our new product; expanding to the next city; improving customer service) even over Optimizing existing operations"

Just say: Big bets even over Existing ops. You can write down what the big bets are, and what you mean by "existing operations," in other documents. The goal with compression is to make something catchy and portable that simplifies decision-making. The more additional noise you apply to qualify the signal, the less portable your strategy becomes.

And another thing...

I've never tried this in practice, but I expect that this same construct would work with Bad Thing A over Bad Thing B.

"Reduce salaries even over Reduction In Force"

Style 2: Maximizing Two Good Things

Back in 2014 (I think?) the brilliant Debra France of W.L. Gore came to visit me at Undercurrent. We were talking about the style of strategic compression described above, and she made the remark, "Picking one thing over another is driven by a scarcity mindset. It's pretty old-fashioned, don't you think?"

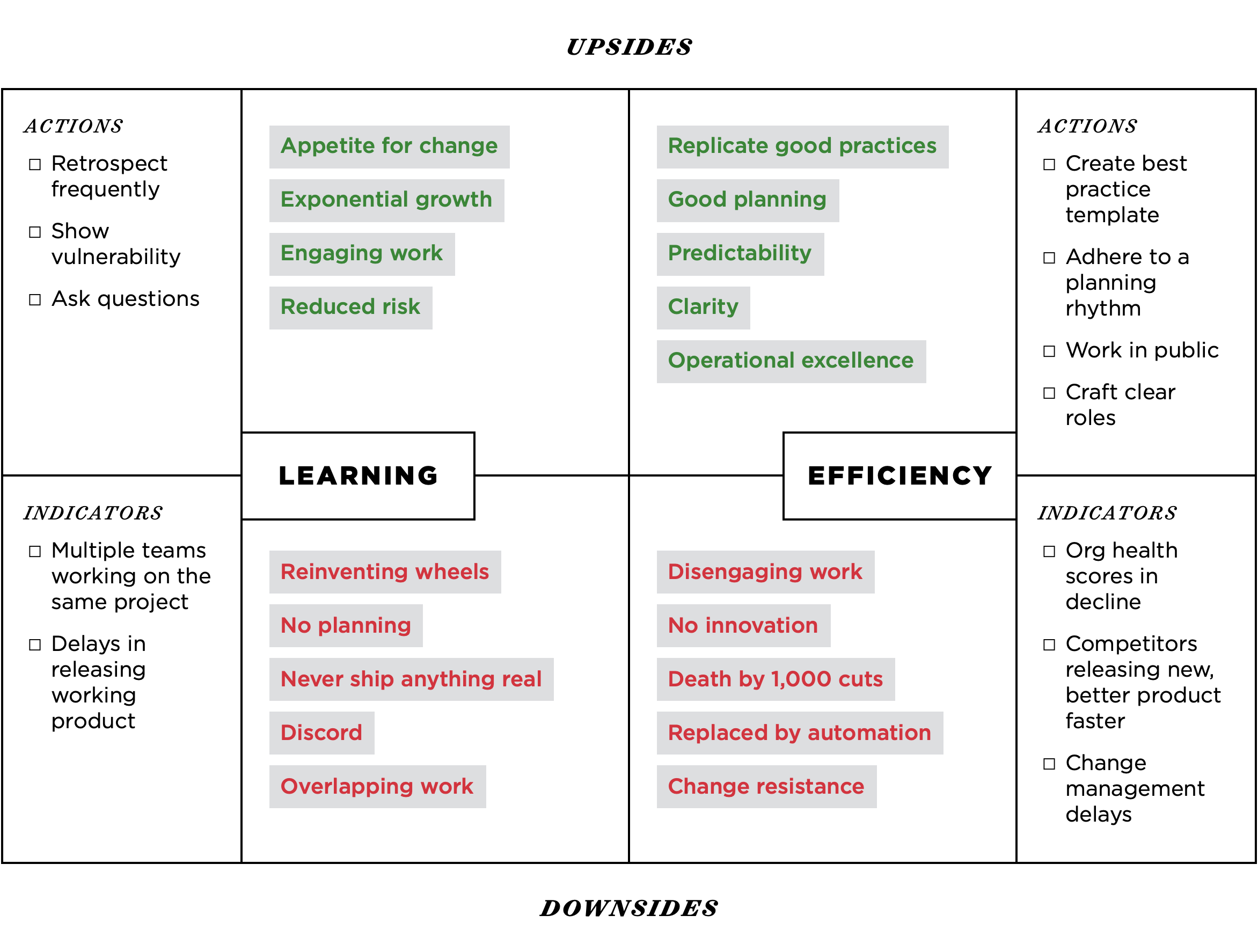

Debra showed me how to identify the good and bad that are created by absolutely maximizing one end of a given polarity. Over-optimizing for openness over closed-ness comes at a cost, and we should be able to figure out a way to get the best of both worlds. It's pretty straightforward to do, once you've done the hard work of identifying the polarities that are driving challenges (and successes) in your work. Just make a 2x2, with the polarity along the X axis, and upsides and downsides along the Y axis. Fill it in.

Then identify what you (or the team) are going to do in order to pursue the upsides for both poles, and what signals you're going to watch for that might indicate you're getting the downsides of either pole. Assign the actions, and consider dashboarding/tracking the indicators.

How-To

This compression technique works equally well for individuals, teams, and entire organizations, and the method for getting to them can be as simple as, "the highest-paid person writes them down" and as complex/drawn out as, "we ran a full-scale program to get to cross-org agreement on these things." The "right" way to do this is probably somewhere in the middle, and should always involves the following steps:

Step 1: Get clear on boundaries

Write down:

- For whom or what these strategies apply;

- From what authority they originate; and

- How long the strategies are in force.

Be as clear and precise as you can be.

"In my role as President, I'm setting the following strategies for the whole of our North America division for Calendar Year 2022.

"For the next quarter, the Website Team is collectively agreeing to abide by the following strategies on the new .com launch; we will get together in the first week of Q2 to assess and adjust."

Step 2: Assemble and review high-quality input

Pull together a range of data, anecdotes, and examples to help ground your thinking in external and internal signal. It may occasionally be appropriate to work from your own opinion or point of view – say, when you're just starting out! – but the act of assembling data before making judgments is a good habit, and a wonderful group activity. With a few people silently jotting notes on post-its or a shared whiteboarding space (a simple Google Doc is wonderful for this!), in the span of 10 minutes, you'll have a robust picture of what's going on in the business.

Step 3: Make a lot of options

Because the wording of these things is the magic and getting the right wording for anything is quite difficult (let alone something that is intended to guide human behavior), you want to generate a wide variety of options from which you can select, mix, and match. Brute force is the way to go here: use whatever medium allows you to quickly write down as many ___ even over ___, or ___ and ___, as you can in 5 minutes. I like post-it notes for this purpose, but again, a Google Doc/Google Sheet will do for the typers and remote workers.

Step 4: Select a handful to try

Now, pick a few. If you're the boss, and you've followed the steps above, you should feel confident to go ahead and pick the ones that make the most sense to you. If you're working as a team, anonymous voting should give you the data you need to make a clear call. Or try the election process.

Step 5: Test immedaitely

Test them by trying to write down a few commitments, action items, or projects that you can make, or that would change as a result of putting these new strategies into place. If it's not obvious that things are going to be better (or at least a little different) after adopting them, they probably need a little work or amendment.