Less Strategy, More Structure

Explaining why big, transformative top-down projects never seem to work, and two simple recommendations to fix the glitch: less strategy; more structure.

I see this pattern over and over again:

- Senior leadership team of BigCo struggles to find a path to growth

- BigCo hires consultants to frame out strategic initiatives, and to project their impact on earnings and growth; these initiatives are illustrated in impressive detail, occasionally including prototypes with feature-level detail

- Inevitably these initiatives will number between 7-15, including powerful execs’ pet projects; there are probably 5 new product categories, 2 new business models, 1 IOT idea, and a few process improvements

- The senior execs charter teams to work these initiatives with a blank check and smile: “Do whatever you have to do to get this done! Work differently! Maybe try agile?”

One of three things usually happens:

Thing one: Team can't deviate from the path

The team discovers that the big idea pitched by consultants isn’t so big after all — customers don’t want it, or someone else in the market is already doing this idea at a price the company can’t match. Because the big-picture Transformation Initiative has already been sold in to investors, the team isn’t allowed to pivot (even though they were probably told to use Agile or Lean Startup methods). So they launch the idea anyway, and it fails. Everyone loses.

Thing two: Dueling false-starts

Another team in the org is already chasing this idea, and when they hear about it, their senior leader blocks the new team’s progress. The new team members, chosen because they were rising stars in the org, grow frustrated. The projects they were working on before this new initiative have already stalled. The other team grows frustrated, too — they’ve taken their eye off the prize to fight internal battles. Everyone loses.

Thing three: We actually need systemic change

It turns out that it’s impossible to get the initiative off the ground without significant changes to “how things get done.” Procurement, legal, IT, and marketing struggle to keep up with the new team and grow to resent the change process, the new team, and senior leadership (after all, they’ve just been doing their job!). The sales org resists: the new team is selling disruptive products to their customers, distracting them from their current deals that were just about to close. Everyone loses.

Obviously, sometimes this mess works itself out, mostly due to individual brilliance and heroism in the face of long odds, or a lucky M&A move. But usually, this pattern repeats on a semiannual basis in a desperate bid for growth.

Why this pattern?

This pattern is all but unavoidable. It's hard-coded into the essential fabric of the firm, and has been so since the DuPont family ('n' friends) professionalized management more than 100 years ago: the entrepreneurial-operational split between capital and labor.

Capital owners are intended to make big-picture entrepreneurial allocations of resource to anticipated future market needs, and labor makes that strategy operational by executing tactics. If you're going to make these big-picture, capital bets, you need good forecasts. But even the best forecasts are just forecasts.

If what I've seen is anything like "normal," strategic business planning processes take something like ~6 months from kickoff to approval and handoff to divisions or teams, with anticipated launches of new or amended products, brands, features, etc. slated for the 18-24 months to follow. Add a 50% overage and the predictions need to be accurate for more than 3 years. Technology, consumer expectations, new competition, regulation, even the executional capability of the org – the forecasters have got to get a lot right in that timeframe. It's way too much to get right, and the act of trying to get it right actually causes the problems: it creates an overcommitment to a single path forward; it's necessarily disconnected from the day-to-day transformation efforts underway in the business and creates duplicative plans; it never assumes a truly discontinuous change in operating model.

The alternative approach combines a shift in strategy and a shift in structure, both enabled by technology.

Strategy: Less, but bigger

To borrow from Marshall Goldsmith: leaders are often guilty of providing too much value. Because they're so smart and successful – and I write that without any sarcasm whatsoever; it's true! – they get used to prescription, when description will more than suffice.

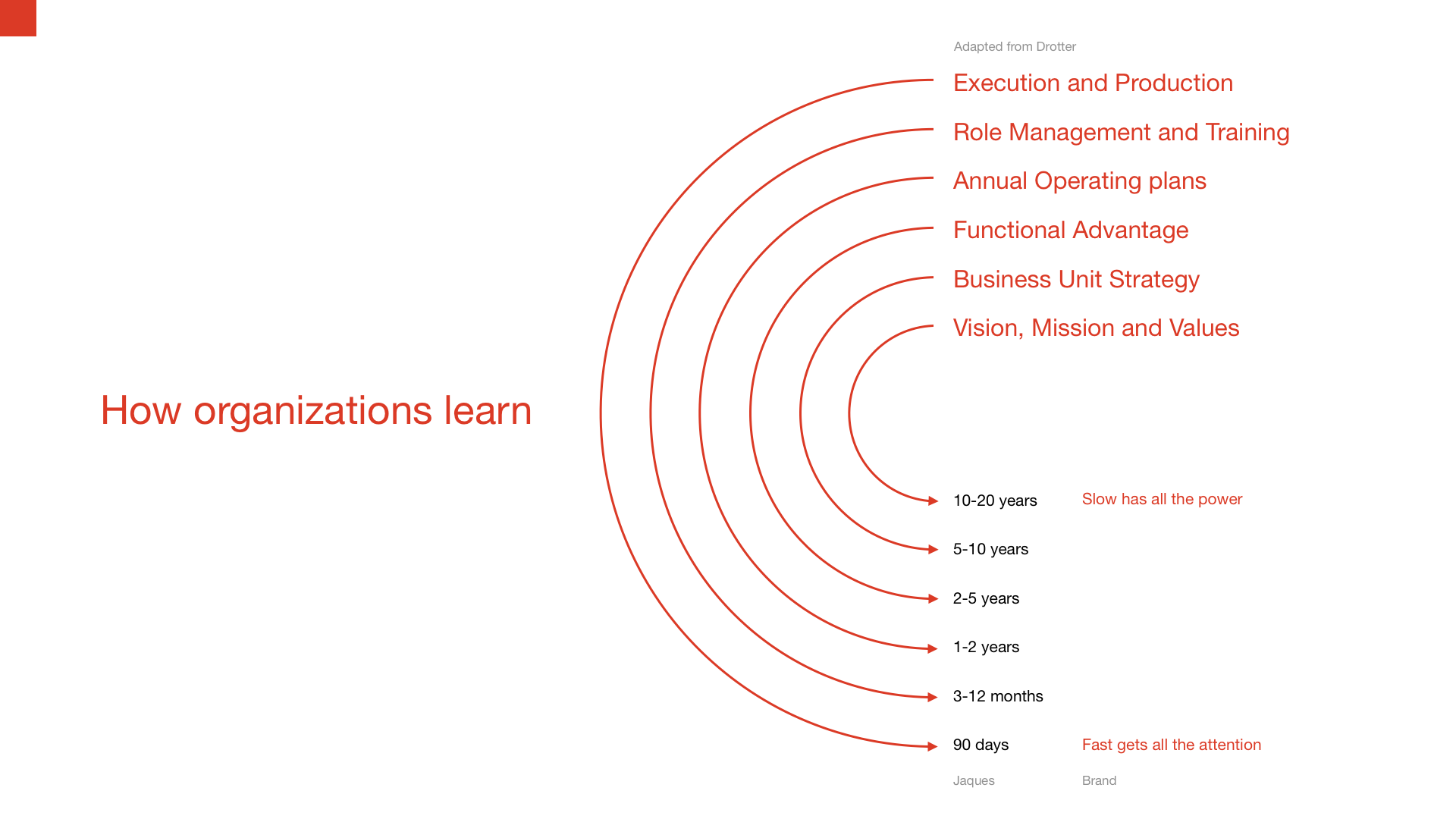

When working with an executive team recently, we unpacked their decisions from the previous year, and found that the majority of them shouldn't have even made it to their radar. The org should have processed those decisions without their input. Their focus should be tighter, on bigger-picture stuff that can only be resolved at the slowest-moving, most powerful pace-layer: mission, vision, and values.

Less, but bigger.

Instead of commissioning consulting decks to plan for the next 5 years, why not charter teams to take on the big challenges that the org is facing? Or hand that challenge to a business unit or function? Give them the autonomy to go make the necessary changes. Work with the functional leaders to ensure they're actually pushing forward and not holding on to The Way Things Are Done Around Here™. Execs will only get that stuff done if they're able to focus on the big stuff.

Structure: More, but smaller

I've mostly seen this problem in big, complex organizations that are matrixed with product or category assuming the leadership role, and functions playing support. The matrix org was designed to replace autonomy with consensus as the operating mode (Litzinger, et al. 1970), and this consensus has an ossifying effect on the status quo. Without clear ownership and authority – because the point is to get folks to go together – creating new, breakout work is next to impossible. How are we going to get everyone to agree that this new thing, whether a new brand, disruptive feature, or process reinvention, is the right idea? We're not.

There's another way, though. In all the OD texts I've read, network-first organizing is derided as impossible to pull off at scale: it's too informal; the lack of formality and top-down reporting structure makes it too hard for senior leaders to control or manipulate; constant change and localized adaptivity give rise to a massive information-sharing and knowledge-management burden. My experience is that these things are already more or less true in large, matrixed orgs anyway. The "informal" org is as powerful or important as the formal one. The scale of the business is too hard to control no matter the mechanism. The information-sharing burden is already high.

So why not try something different?

Shrink the size of the pieces to something more manageable – teams – and invest in the necessary technologies that allow them to coordinate and be coordinated by leadership. The entrepreneurial-operational split is an important information-processing hack. It keeps the org focused. But our big, matrixed structure gets in the way of effective big-picture entrepreneurship and efficient tactical operations. A network of teams would do better.

More, but smaller.

Comments