Integrating Loyalty

So I’ve been thinking a bit about loyalty over the past few months.

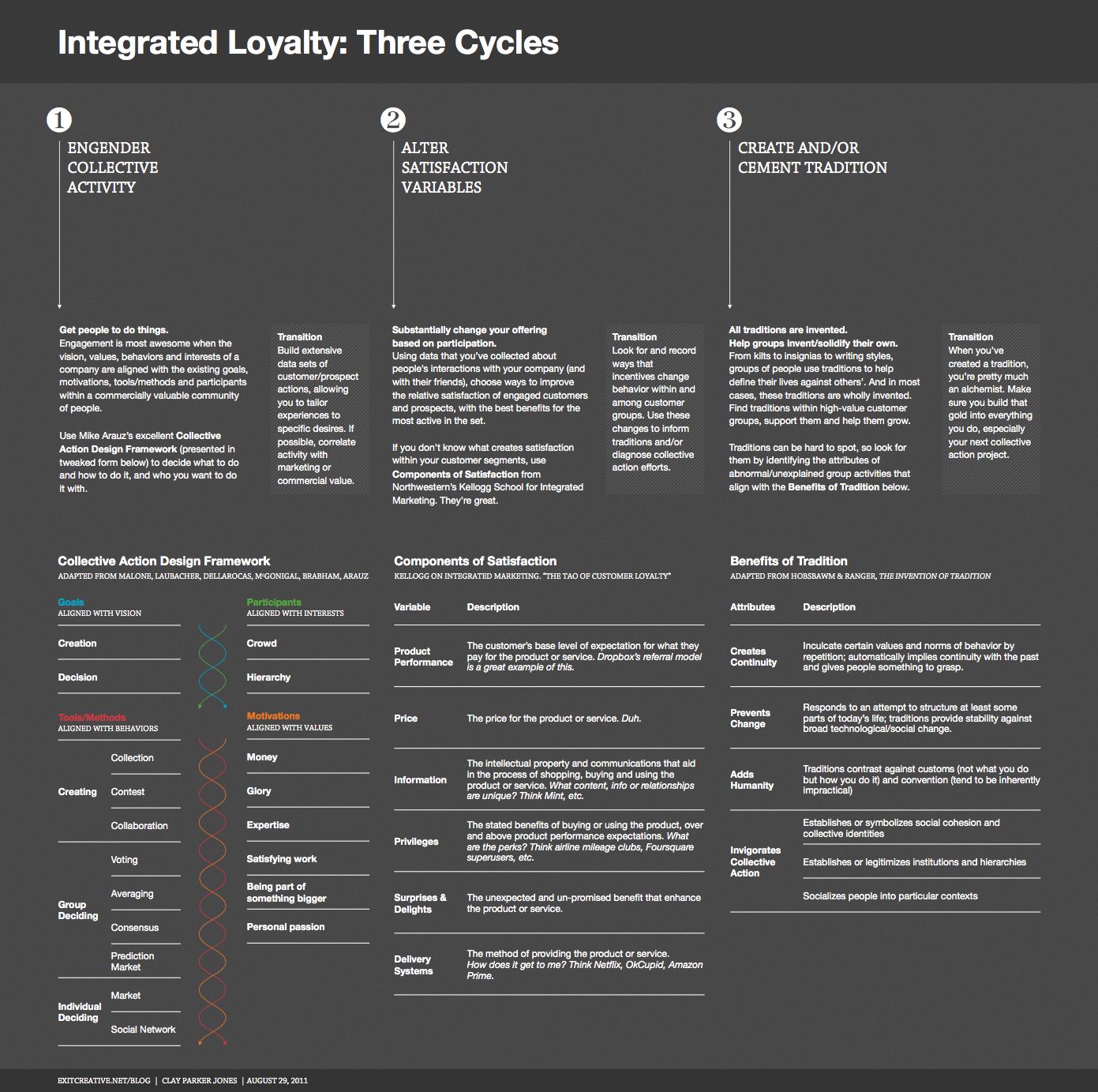

More or less, I was thinking that a new, cool perspective on loyalty programs could be made up of three important parts:

- A part that gets people to do things with and for each other

- A part that uses known satisfaction variables to make people’s experiences better if they do things that are valuable (beyond referrals)

- A part that at least recognizes, or at best creates traditions within groups of people

After thinking about it some more, I still like the framework.

I’m planning to post more on this during the week, but I think there are three key cycles for creating a good, modern, integrated loyalty execution.

- Create Collective Activity

This is pretty straightforward. If you’re creating a program – or ideally, a product – that creates collective action, you’re creating an amazing foundation for a next-generation loyalty program. If people are working on behalf of their group and in so doing are furthering your company’s cause, the work those people are doing should be rewarded with something. - Alter Satisfaction Variables

Now for the cookies. The work I put in, either by using goods and services frequently or by pimping the brand on the internets, should snare me something delicious. And when I say delicious, I mean it should tangibly change the way I experience your company. Born-digital companies get this, and crush it (generally), and pre-digital companies tend to stink it up. - Create and/or Cement Tradition

Now for the new shit, and probably the thing most likely to cause an argument: creating traditions. As far as I know, brands don’t tend to get into the tradition “discussion”, if there is one, and it’s mentally difficult for me to recommend to people that they should be out there trying to make a tradition stick with a bunch of people. But in little ways, it’s happening, and if a smart/adaptive program should be able to take advantage of tradition when it appears.

Create Collective Activity

One of the big, important pieces of my approach to marketing strategy (more on that next week) is a belief that brands should do really amazing things for people. This can take the form of a delightful piece of short-format cinema, or it could be some interesting interconnected system of digital things.

But if we’re talking about things on the internet – and what doesn’t fall into that category in some way? – ultimately those things should be designed to create action. But like most things that reverberate in the strategy twittersphere, “designed to create action” is pretty easy to agree to.

It’s the “How?” question that’s really difficult to answer.

Dueling Approaches

Our dear leader, Aaron, has a great book on getting people to do things that they might not necessarily want to do, or that they don’t have the skills to do on their own. I’ve seen this done exceptionally well, but it’s definitely an advanced move.

In my experience, success comes from aligning the thing you want people to do with something people are already doing. For me, it’s the easy pickings, the foundation upon which everyone should be building.

Sidebar: Ad Spending

To that end, I’ll never recommend buying an ad on a site where people just read shit, even if that shit is wonderful, engaging and superbly written shit. If it’s a place where people go to DO things? Yeah, give them all your (ad) money.

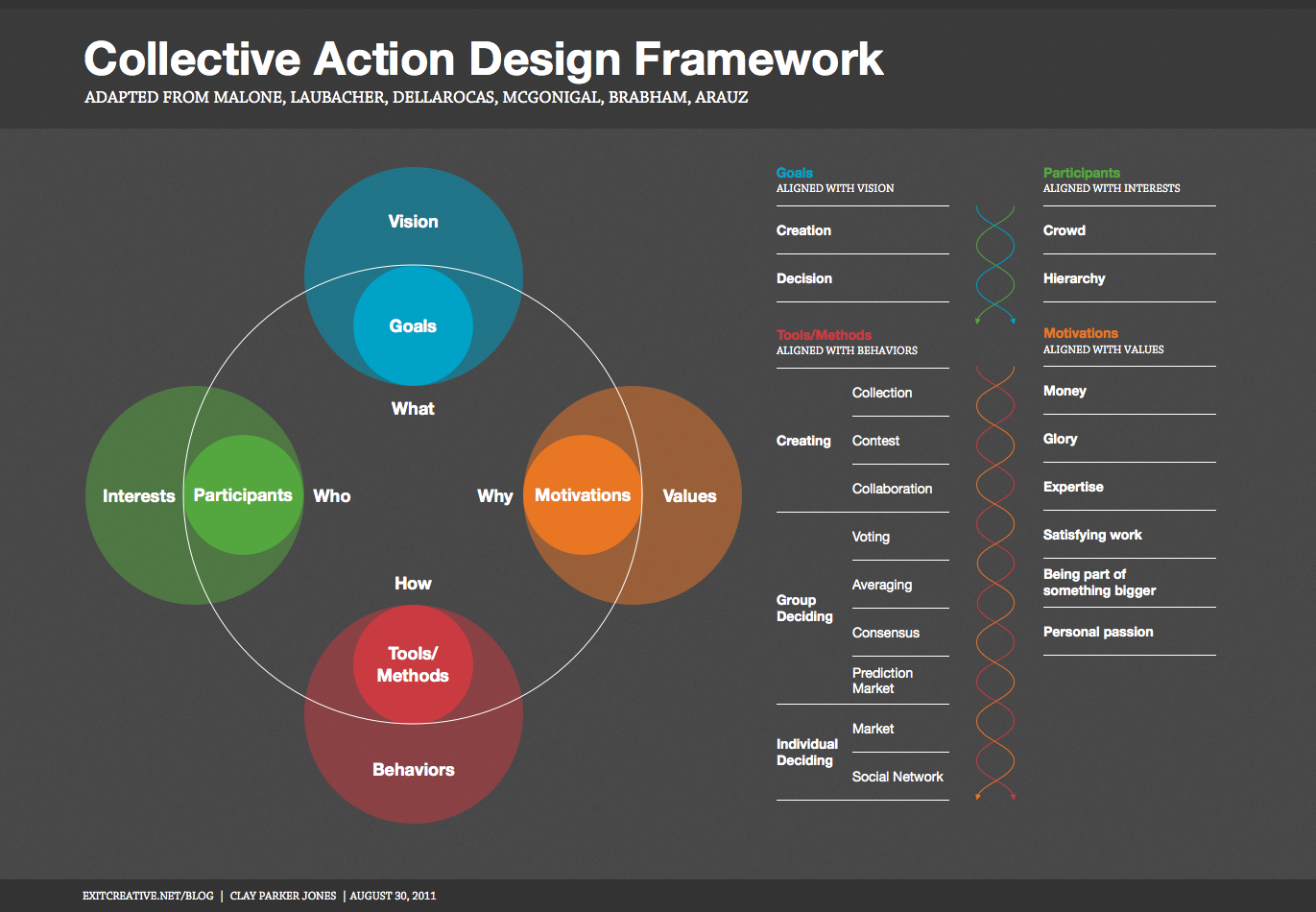

Last year, my delightful and brilliant colleague Mike Arauz put together something he called the Community-Centered Collective Action Design Framework (CCCADF?), a synthesis of the following:

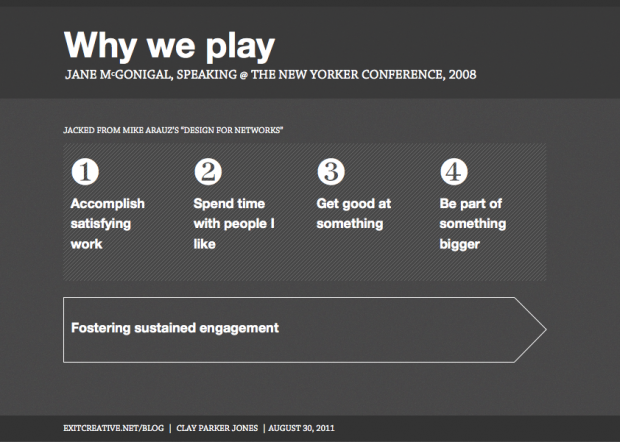

These four things are why people “play”, but in my mind, they’re why people do anything they don’t have to do. We use this all the time. Mix one part of the above with…

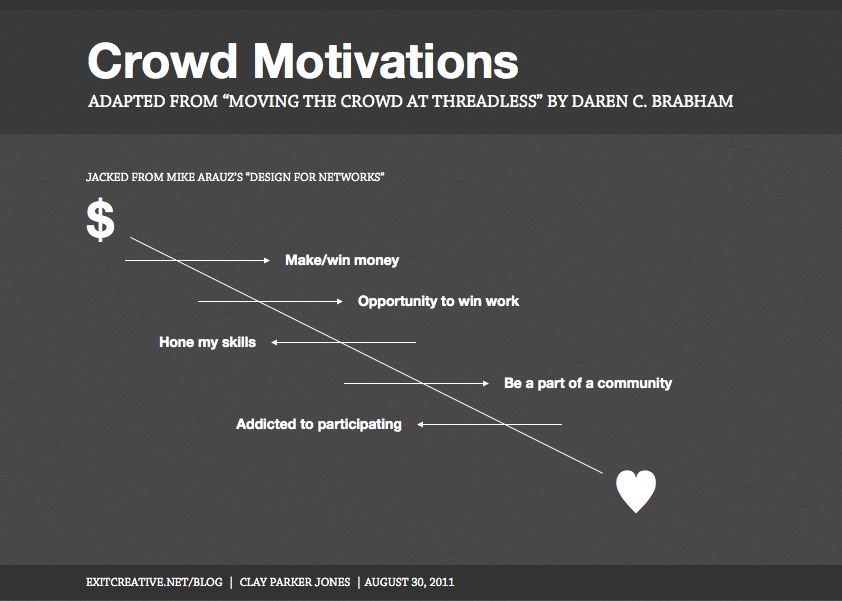

These are from a paper about why people use Threadless, (PDF) and are pretty spot-on. Add to that some core elements from MIT research on collective intelligence, and you get…

The Collective Action Design framework is, to me, the fundamental tool that strategists should use to test and validate their recommendations when those recommendations hinge on creating action in a group of people. Nice work, Mike.

It’s pretty straightforward to use: do your homework, and fill in all the bubbles.

Sidebar: Interest vs. Demographic Groups

Demographics and psychographics are tough. I’m not sure they do much of anything in the digital world. So when it comes to answering the “who” question, work on defining the thing that holds the community together.On the internet, “Who” is defined by interest and nothing else.

Need a glossary? Here you go, stolen from Mike’s post on the topic:

Interests

What is the shared interest that brings these people together and defines their collective identity? (Hint: the answer is not “our brand”)

Vision

What is an aspect of our world that this community would be inspired to help change? (Hint: it can be big or small, as long as it’s a specific outcome that is inspiring to the community)

Values

What are the beliefs that guide this community’s decisions? (Hint: look at the kinds of information that strengthen bonds between members and gives members status within the group)

Behaviors

What are the common modes of interaction and communication within the community? (Hint: pay closer attention to what people do, than to the platforms that enable it)

Goal: What specific collective action is the group contributing to?

- Create – the group needs to create something new

- Decide – the group needs to choose

Participants: Who is the group of people who will be working together?

- Crowd – a loosely organized, widely distributed group of people, typically unrestrained by place or time

- Hierarchy – a group organized by a management structure, with specific roles and responsibilities for each participant

Motivations: Why will each person within this network be compelled to participate?

- Money – in exchange for a monetary reward

- Glory – for the opportunity to gain public recognition

- Expertise – to hone their skills and get better at what they do

- Social – to spend time with people they like

- Satisfying work – the feeling of accomplishing meaningful tasks

- Be part of something bigger – the sense that they are contributing to something bigger than themselves

- Personal passion – because this is something that they love to do

Tools/Methods: How will the group be enabled to participate?

- Collection – each participant contributes in small pieces on their own

- Contest – used when there is a limit on how much needs to be created

- Collaboration – used when individual contributions necessarily affect each other

- Voting – each participant votes for their favorite choice, most votes wins

- Averaging – each participant rates independently, and the aggregate ratings are averaged for a final rating

- Consensus – participants engage in direct dialogue with each other to agree on a precise outcome

- Prediction Market – participants place bets on what they expect to happen

- Market – participants spend money to express their choices

- Social Network – participants trade in social currency to guide and express their choices

This is a model, and as such it’ll break sometimes, but in my usage it works more than it doesn’t.

So, what to do with all this? And who’s doing it well?

There are a few companies doing collective action well, but by and large their efforts are disconnected from their customer masters on the back end. And if the company is doing collective action really well, it’s likely that they’re a born-digital company that has CRM/Loyalty built in to the soul of the company (Quirky, Foursquare, OkCupid, Amazon, etc.)

So how about an old fogey doing well in the new world?

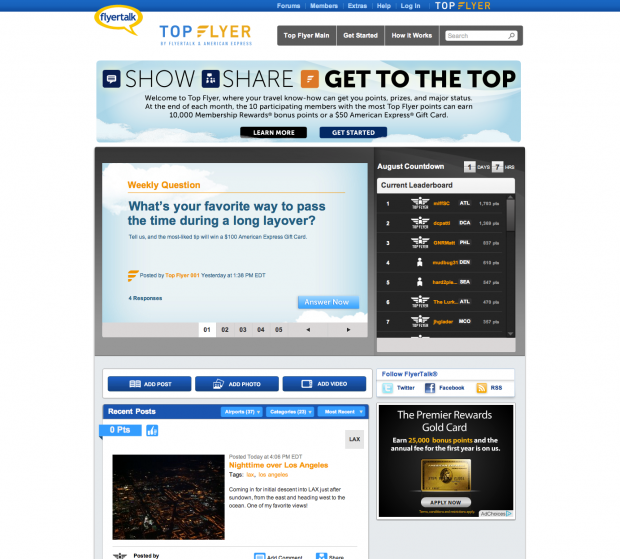

Amex + Flyertalk = Top Flyer

This is great. Or at least, mostly great.

If I were an airline, I’d be doing what American Express is doing with the Flyertalk forums, where participation in Top Flyer group discussions earns you points, and the top point earner gets Membership Rewards points or cash. There’s no reason why I shouldn’t be able to log in to Flyertalk with my Delta SkyMiles number and rack up points for participating.

The Top Flyer activation probably shouldn’t be its own forum and could be more complex in its scoring mechanisms, but…

- It’s well-connected to the interests of the group (improving travel experiences)

- It creates some interesting hierarchy structures that absolutely align to the way forums work (mods, etc. …this could be blown out more, though)

- It would be nice if it weren’t just about “travel know-how” and was more about making decisions for a company (which is why an airline would be perfect for this)

- Its tools and methods are exactly aligned with what’s already happening on Flyertalk

Focus on Action and Connect the Tubes

All of that was a long way of saying two things: when it comes to loyalty, you should focus your digital efforts on creating engagement that’s built on existing motivations, interests, behaviors, and tools; those efforts should connect back to a customer master so you can incentivize valuable behaviors.

Otherwise, two things are happening.

- You’re buying impressions and you really ought to be buying something more efficient for that.

- You’re creating action for action’s sake, which is cool engagement but inherently disconnected from the sale.

Both of which are a bummer, right?

Altering Satisfaction Variables

Now for the traditional, business school stuff: variables of customer satisfaction.

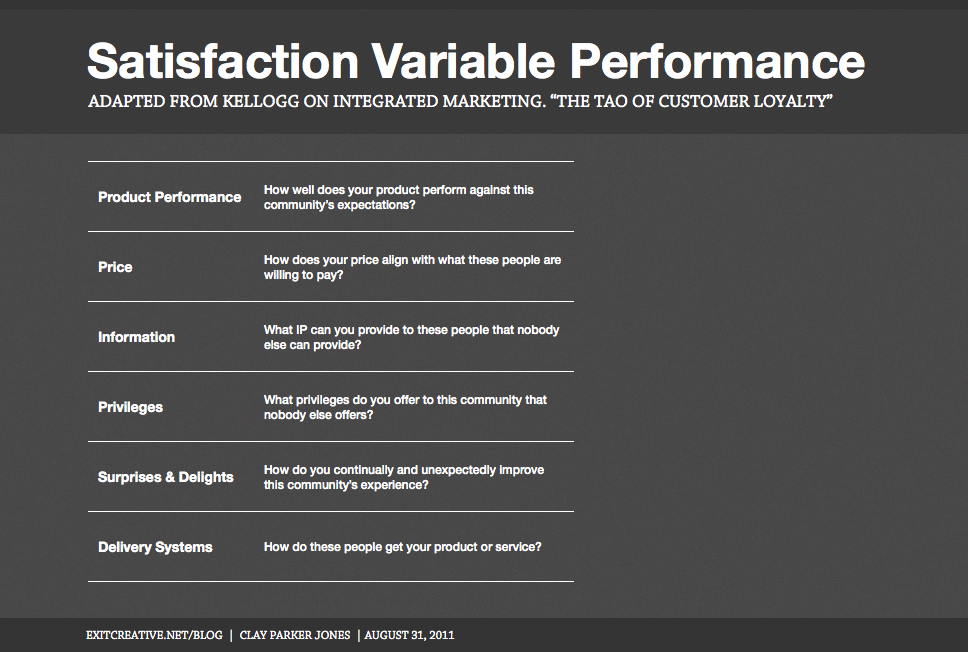

Satisfaction among a set of customers, no matter the business, seems to be composed of six key variables:

- Product Performance: Does the thing I’ve purchased live up to my expectations?

- Price: Does the price of the product match up with its performance relative to my needs?

- Information: Does this thing give me some mental benefit that I haven’t had before?

- Privileges: Am I afforded some unique opportunities, above and beyond what I expected of the product?

- Surprises & Delights: Is there some un-promised and awesome thing that happens as a result of my using this thing?

- Delivery Systems: How do I receive this thing?

Differentiation from competitors can be – well, kinda has to be – created in multiple categories, and the more differentiation, the better.

You knew that.

But what we’re talking about here isn’t just general best practices for business, it’s building integrated loyalty systems. Yesterday we covered the “How?” question for collective action, and today we’ll cover the “How?” question for altering satisfaction variables, based on the collective action that you’ve created by doing something great for your customers and prospects on the internet and in the real world.

The first step is to map how your product works against the six components of customer satisfaction, according to the segment of people who use your product or service that you’re targeting with your efforts in the collective action space.

You should probably do research to find out how you’re doing. Don’t guess.

From there, I’ve adapted a pretty straightforward process from Dawn Iacobucci and Bobby Calder’s Kellogg on Integrated Marketing for deciding what kind of benefits make sense to provide to the people that engage with you. You should buy that book, by the way. It’s super dorky, but really helpful.

Iacobucci, Calder et al. provide seven phases:

- Set the vision: Where are we going?

- Identify best customers: What’s important?

- Value them: What are they worth?

- Set goals: What will we accomplish?

- Set attributes: What do I do for them?

- Communicate: How do I get the word out?

- Evaluate: Did it work?

I’ve dropped the last two as they ought to be intrinsic to the program; measurement and communication shouldn’t be “phases” but should be core to what’s going on, and I’ve simplified it/made a few tweaks here and there.

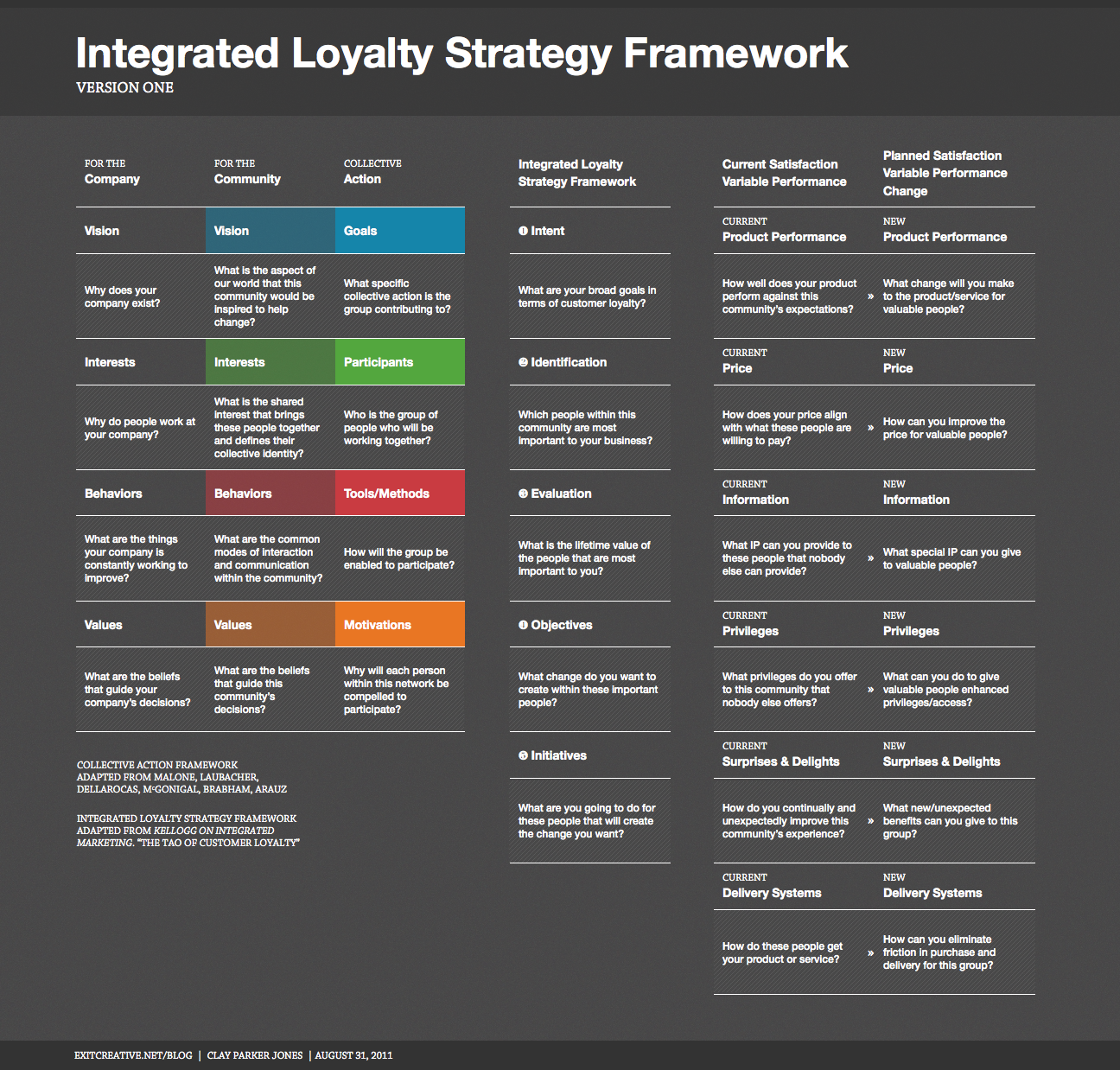

So with that in mind, I’ve layered my revisions to their phases with the Collective Action Design Framework and the Satisfaction Variable Performance thing:

Clunky name, I know. You’d probably fill this thing out, like a worksheet. Answers in every box inform every other one, I imagine, so it’s likely that you can’t just do strategy by numbers here.

This is intended to be used for a single group of people, not to describe your broad vision for loyalty. You might have multiple targets and multiple ways of engaging them, and that’s okay. Just be sure to map them out.

So here’s how to use this framework.

Intent: What are your broad goals in terms of customer loyalty?

Do you want to increase loyalty? Do you like having customers? I hope so.

At its broadest scale, what are your intentions in the space? Write them down.

Identification: Which people within this community are most important to your business?

The biggest surprise in my business-life is that most companies don’t have a clear or shared understanding of who of their customers are, let alone who among all their customers are the “best.” Define best as you will. Sure, there’s a colloquial understanding, or an aspirational understanding, but hardly ever clear-cut, simply explained and collectively held knowledge across everyone in an organization.

So in the identification piece, for a particular community of people that are your customers and are interacting with you in the social space, the key outcome is to be able to agree upon and write down the groups of people that are important to your business, either for marketing reasons or commercial reasons.

Evaluation: What is the lifetime value of the people that are most important to you?

Even harder challenge: tell me, tell anybody the actual lifetime value of the people you’ve identified as important to your business.

What value do they provide? How do they provide it? Do they buy a ton of your product? Do they buy a little of your product, but they buy it consistently over a long period of time? Do they help you improve the way you do business? Do they spread your messages to all their friends?

Sidebar: Non-sales (or Marketing) Value

There’s a million ways that people provide your business with value, and when you’re considering the different ways people do it, don’t forget about things that don’t explicitly tie to sales. I know, I know. But it’s important.

Key outcome of the evaluation piece: for the people that are important, work to define in absolute terms how much value they provide to your organization.

Objectives: What change do you want to create within these important people?

You’ve now officially left the really difficult part of the program. If you know who is important, and you know why they’re important, deciding on the change you want to create is easy.

Sidebar: Objectives

And yet, objectives frequently suck. Probably because people don’t do their homework. If it’s not measurable, it’s not an objective. Anyway.

With the community of people in mind, decide what kind of change you want this integrated loyalty effort to produce. You could make the group buy more frequently. You could reduce the likelihood that a valuable customer would decide to not buy from you again. You could get certain, vocal segments to talk about you more. You could get more information on a segment you don’t know much about (scary, but you could do that). You could grow the number of people in a certain segment, as defined by purchase habits, beliefs, etc. You could find people that are similar in some way to your most valuable customers (look-alikes) and try to get them to be more like your best homies.

Outcome: One or more measurable things that you want to achieve. Almost done!

Initiatives: What are you going to do for these people that will create the change you want?

Now for the fun part, but probably a contentious one within an organization: deciding what valuable thing you’re going to give to people when they give attention, money, or some other valuable thing to you. Using the satisfaction variables, choose one or more things to change. To make it amazing, choose things that are tied to the Collective Action Design Framework.

In yesterday’s example, trading Membership Rewards points for participation in a reward-point-obsessed community makes a ton of sense. In my mind, that’s part Price variable and part Privilege variable. Most loyalty systems seem to fall along this spectrum, predominantly because it’s harder to vary the other elements.

But you’ll be better off if you’re more creative.

- Dropbox is able to vary Performance by giving people extra space for successful referrals.

- Zappos varies Delivery by speeding up the shipping process for people that are likely to spend more in the future.

- They’re not loyalty programs per se, but Mint, Netflix and OkCupid give more Information to people that give them more information.

- Local bars and restaurants vary Privilege and Surprises/Delights by hooking regulars up with more attentive service and a freebie now and then.

- Bank of America (and I assume all banks, but I know BofA does this because I worked in their call-center once) varies Privileges by giving special, live phone support to customers that have multiple accounts with the bank,

- My aunt and uncle use an unofficial credit system to ease Delivery for frequent customers, putting a card with their name on it in a box near the register; if you are on a ride and need a tube, but are out of cash…no problem.

So the outcome for this final piece is to pick the variable most aligned with what the community wants, and improve it in some obvious way. These are your initiatives, and you should work with your partners and internal resources to get them done.

And unless you’re the owner of a small business, you’ll probably need to use the outcomes of Identification, Evaluation and Objectives to substantiate your decision in financial terms, but that should be easy at this point.

Onward and upward from there!

Creating Tradition

So…marketers creating traditions. As I said on Monday, that’s a terrifying recommendation in that it could go so humorously wrong.

And that recommendation was expectedly contentious, with recommendations from smart folks to consider changes in terminology for that space.

So while I agree it needs a considered approach, a few thoughts and stories about tradition(s) that I hope provide direction and ideally change your mind.

“‘Invented tradition’ is taken to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or sumbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behaviour by repetition, wich automatically imples continuity with the past.”

Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition

Kilts, Tartans and Bagpipes are Made Up

We read this book in college – or at least, I was in a class where it was required that I read this book, and I heard it discussed in the lectures that I attended (I was a bad student) – that blew my mind.

Mostly because it explained how kilts and other associated “Highland Traditions”, including tartans and bagpipes, were invented and established in the late 18th and early 19th century by a variety of folks, driven by nationalist and commercial motivations.

Apparently this happened in three stages:

- “Cultural revolt against Ireland: the usurpation of Irish culture and re-writing of early Scottish history, culminating in the insolent claim that Scotland was the ‘mother-nation’ and Ireland the cultural dependency…

- “The artificial creation of new Highland traditions, presented as ancient, original and distinctive…

- “The process by which these new traditions were offered to, and adopted by, historic Lowland Scotland.” (Hobsbawm & Ranger, locations 225-241 on your Kindle)

The details of this are fantastic, odd, and if you like this kind of thing, fairly romantic. Worth a read.

But for the sake of expediency (we’re already 3,498 words into this series) it’s worth pulling out of that passage three key stages for the formation of a tradition.

- Position one group against another group

- Create some group of traditions that solidify your group identity

- Incentivize the uptake of those traditions within your group and beyond

Next story.

We Know Diamonds are Made Up. But How?

A couple days back, Kottke linked to this amazing article from a 1982 issue of The Atlantic, called “Have You Ever Tried to Sell a Diamond?”

I knew that the integration and collusion within the diamond industry helped them create and sustain high prices for an otherwise not-so-expensive-to-produce thing.

But I always considered the advertising an afterthought.

Turns out DeBeers and N.W. Ayer created a strategy in 1939 that amounted to the creation of multi-decade campaign to change the psychology around diamonds, to “inculcate in [young men] the idea that diamonds were a gift of love: the larger and finer the diamond, the greater the expression of love. Similarly, young women had to be encouraged to view diamonds as an integral part of any romantic courtship.” (Epstein)

Their new-media (films, high-concept full-color print, no direct sale, etc.) efforts worked, reversing a sharply downward sales trend in around three years. But they weren’t done.

Directly from their strategy plan nearly a decade (a decade!) later, “We are dealing with a problem in mass psychology. We seek to…strengthen the tradition of the diamond engagement ring – to make it a psychological necessity capable of competing successfully at the retail level with utility goods and services…[with a target of] some 70 million people 15 years and over whose opinion we hope to influence in support of our objectives.” (Epstein)

20 years out from the start of the campaign – imagine writing this in a report to a client – “Since 1939 an entirely new generation of young people has grown to marriageable age. To this new generation a diamond ring is considered a necessity to engagements by virtually everyone.” (Epstein)

Ridiculous.

So by my calculations, national traditions seem to take somewhere in the range of 50-75 years to create, and the creation of a tradition around a good/service requires a paltry 20 years.

The lesson here: commitment.

How?

It’s clear, at least to me, that participation in the traditions of a culture, be it national or consumption-related, indicates some sort of loyalty to that institution. Sure, you can tell me that in some cases, that loyalty is forced, but that’s a separate debate.

So how do you create a tradition? How do you create multi-decade loyalty in a space where New Hot Thing has vanished in months, not years?

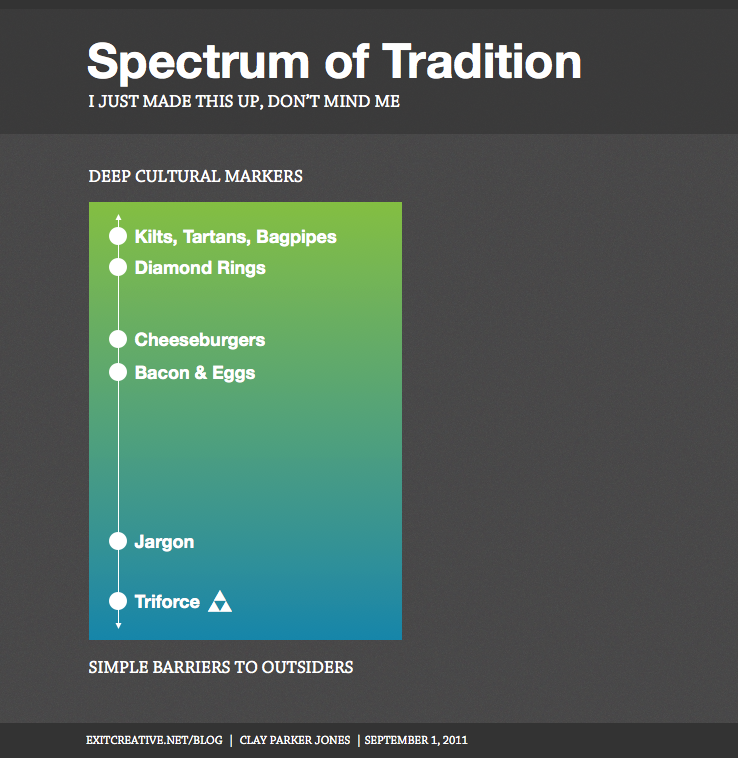

My suspicion is that you look for things that resemble invented/adopted traditions within the community you’re courting (please see Parts 2 & 3, below), and codify those things in the systems that surround your product or service.

Think you have a tradition on your hands? Check it against these four things.

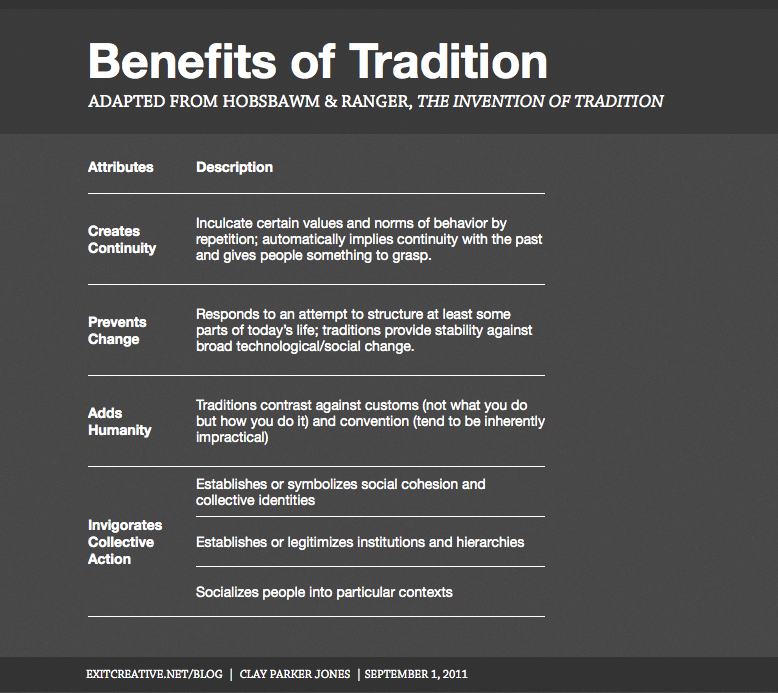

Traditions Create Continuity

Traditions inherently reference some shared history. It might be a fake history. It might be a very recent history. But they reference a history all the same.

Digital Example: Image Macros

Traditions Prevent Change

Societal change tends to produce traditions; as change becomes more rapid, people hold on to little things that help them feel comfortable in new situations.

Digital Example: Economist Comments

Traditions Add Humanity

Traditions aren’t what is being done, but rather how it’s being done. To use an example from Tradition, the wearing of hardhats at construction isn’t a tradition, it’s a requirement. The wearing of powdered wigs and robes? That’s a tradition.

Digital Example? I couldn’t find one. But I’m working on it.

Traditions Invigorate Action

Traditions are markers of a collective identity and are clear in/out signals for a group. As such, they’re an important part of collective action:

- They establish/symbolize social cohesion and collective identities

Digital Example: Chicklets & Badges; go onto a social media/marketing nerd’s blog and check out their sidebar content. It’s likely littered with Twitter follow counts, their ranking in the Power 150, links to their various profiles on other sites, and a badge for their SxSW panel. These all serve to indicate to others in the social media/marketing nerd space that they share a collective identity. - They establish or legitimize hierarchies

Digital Example: Triforce (potentially offensive language); there’s no logical reason, especially on an anonymous board, to have some way of distinguishing newbies from old hands. And yet, it persists. - They socialize people into particular contexts

Digital Example: Forum Jargon; jump into a weather or aviation forum (as I frequently do) and you’ll be inundated by a variety of confusing acronyms and unnecessary jargon words. They serve to keep less-nerdy folk from messing up the rhythm of the conversation.

What now?

So the directive: look for traditions, identify ways that they can be supported in your interface, in the design of the product (and ideally the service surrounding that product), and then incorporate those methods into the next evolution of your loyalty efforts.

Design your traditions to help your customers identify themselves against others (think Apple’s white headphones), tie them closely to the identity of your company and all its customers, and then begin rolling those cues out to the rest of the world.

Domination awaits. In 20-75 years.

Sources:

- Edward Jay Epstein, “Have You Ever Tried to Sell a Diamond”, The Atlantic, February 1982

- Eric Hobsbawm & Terence Ranger, The Invention of Tradition, 1992.

Comments