Designing for Autonomy

Purposeful autonomy has been, and always will be, the main goal of organizing.

I presented the below at the Future of Work meetup in 2014.

As far as we can tell the core reason for organizations today is to grow, serve and leverage networks. This statement also works as a core differentiator between legacy institutions, which primarily exist to serve shareholders, and responsive ones, which serve networks. There are lots of little things that fall out of and support this statement, which I’ll get into later, but for right now this statement feels more correct than anything we’ve got.

And while I’m no expert in the philosophy of autonomy, it’s very clear that it’s absolutely essential to the development of networks. Without autonomy, networks resist formation, and instead lay dormant in traditional frameworks, like “employees” or “customers”. And it appears that there are two conceptions of autonomy that are worth examining in the workplace: the ability to self-direct work, and the ability to work toward a common, socially accepted good. Both provide a desirable foundation for something that Stowe Boyd mentioned last month – unintended order – and drive engagement. If you’re in charge of your destiny, and you agree on the future you’re building toward, more frequently than not you’ll be engaged in the work of the enterprise.

With that, a few things that we’re continually experimenting with at Undercurrent:

Firstly: allowing all teams to reorganize themselves by pushing authority to the edges of the organization. This allows active makers (versus passive managers) to make changes to the way they do work without worrying about approval.

We’ve seen several organizational impacts, two of which I’ll mention here.

- First: the restructuring of an outdated organizational trope that we maintained at Undercurrent (executive assistants). Because we allow teams to restructure autonomously, we’ve seen that admin roles have become distributed and team members that work in those roles have taken a more powerful (and appropriate) seat at the decision table.

- Second: the development of process through teams, rather than through checklists. As a small company run and inhabited by creative types, we traditionally resisted process. By creating clear ownership of work, we’ve reinforced a more natural form of process: moving a product or service from one group to the next.

About a year ago, we drastically raised salaries to bring Undercurrent employees up to market rates for our then-new competitive set: big consulting. And while this ensured a base level of talent density, it didn’t have many other compounding effects. So we recently rebuilt our salary strategy to allow tenured specialists to stay in-role longer at Undercurrent, helping us eliminate the Peter Principle – which I think we’ll all agree is bad for everyone involved. Instead of jumping out of the role you’re good at (Senior Strategist, in this case), just say there, and keep crushing it.

Even with better salaries, a longer in-role runway, and edgy reorganization, we still had too long a feedback loop when it came to salaries and promotions. And when the feedback loop was closed, it was closed with fuzziness. So we’re moving over to ongoing opportunities for base-salary raises, in line with trimesterly success against individual OKRs. The OKRs are set with guidance and help from colleagues, and are designed to be hard-to-achieve and aligned with our purpose. This ends an ongoing cycle of UC gaining surplus value from its employees: UCers gain skills at a rapid pace, and annual salary adjustments are too slow to match their rate of improvement.

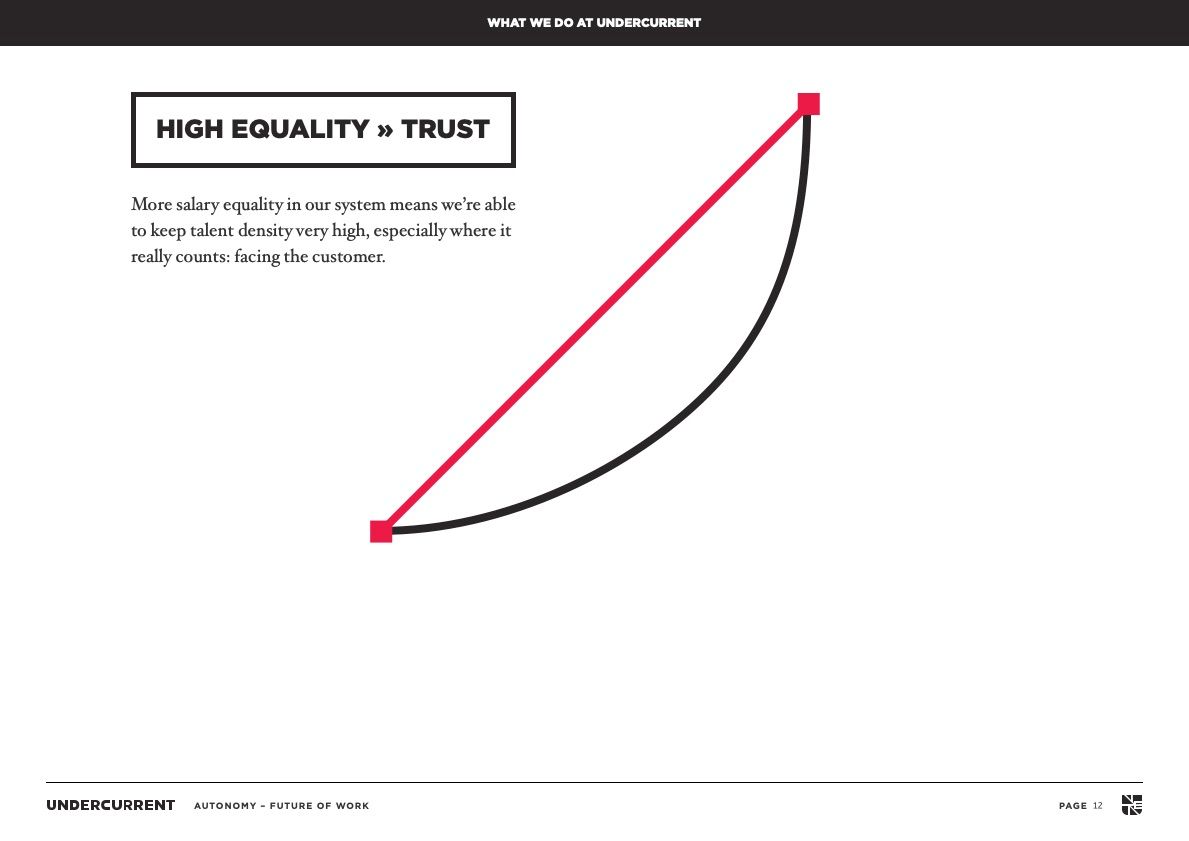

Lastly on the compensation/structure front: we have a much higher degree of salary equality in our (admittedly small) organization than other organizations pursuing similar networks. Most organizations that we know of have almost all the wealth concentrated in the hands of a few individuals, and leverage the work of many low-paid individuals. By maintaining a higher degree of equality, we’re able to offer our network a higher concentration of talent and convey more explicit trust to more people: this means we need fewer processes relative to our peers, and fewer people have the implicit “right” to exert power over others.

Comments