Creating The Conditions

A corporate retreat day organized around three stories, three games, and three new practices.

This is what I delivered yesterday at a corporate offsite in beautiful Calistoga, California. It was a one-day session; the ask from the client was to get the team to think big and consider their business from a clean sheet. My bias is to do that while leaving them with practices that allow them to do this continually after I've left. The title comes from here.

Section 1: Intro

I started with a quick case-study of our current work. It began with a pilot in a single site, immediately after a re-org, where we coached teams toward new ways of working and organizing. Knowing that it worked, but that it was hard to execute on one's own, we spent the next 18 months (up until now!) making things simple and spreadable. The practices are now in more than 60 cities, with thousands of people working in a new way.

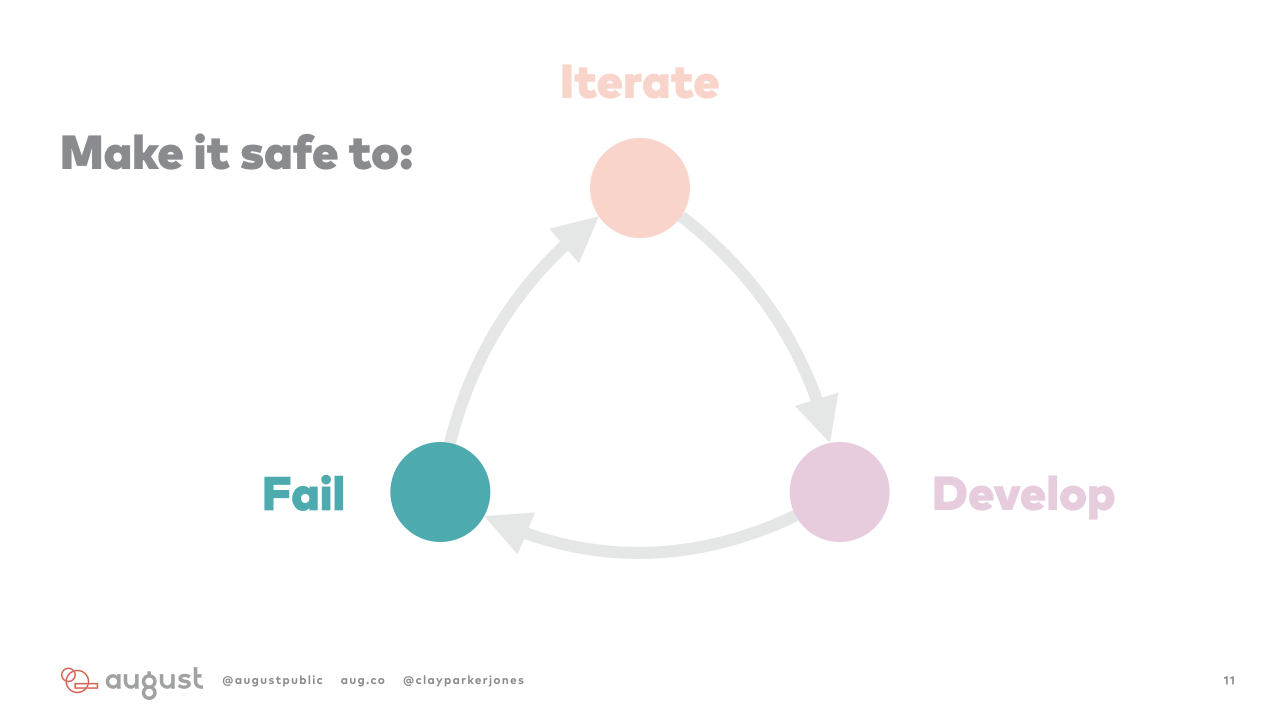

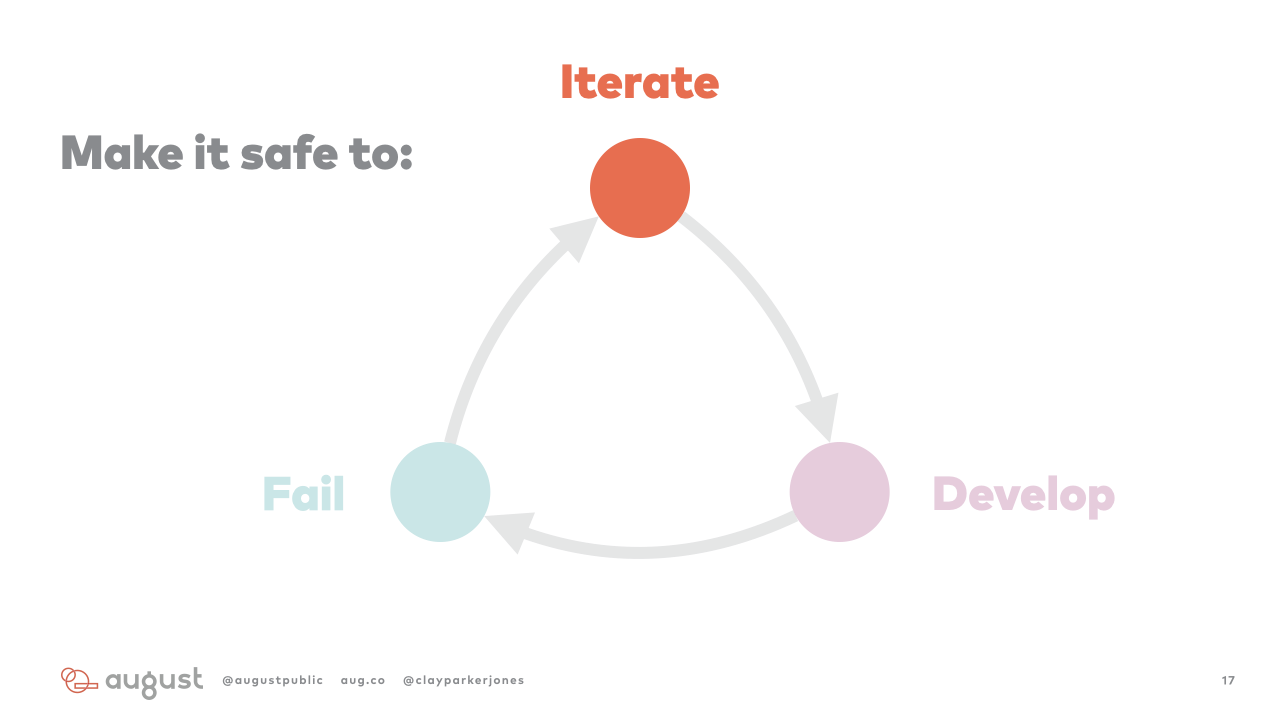

As we roll out a tailored-to-suit suite of small practices across all of our clients, we survey adopters of the practices pre- and post-adoption. We're noticing some patterns. While it's still early days, the factors that lie beneath the change – the reason why teams are able to accelerate their pace 15-30x while improving engagement – are falling into three categories:

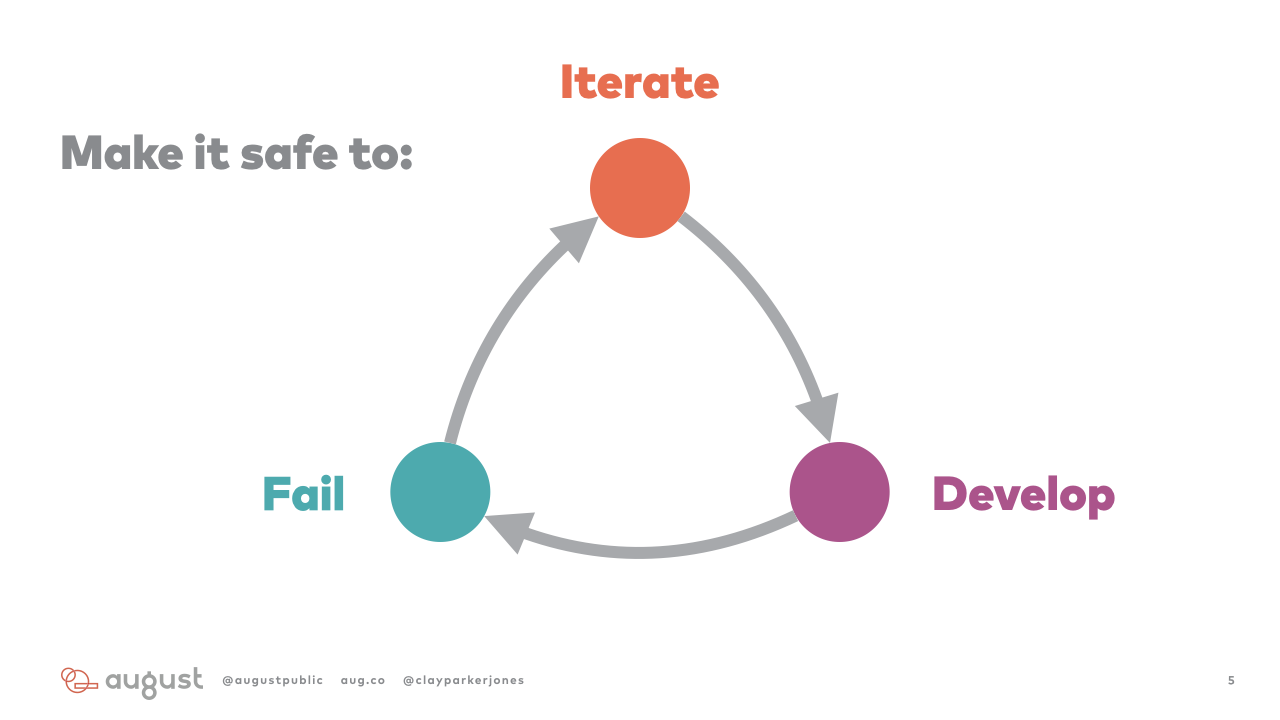

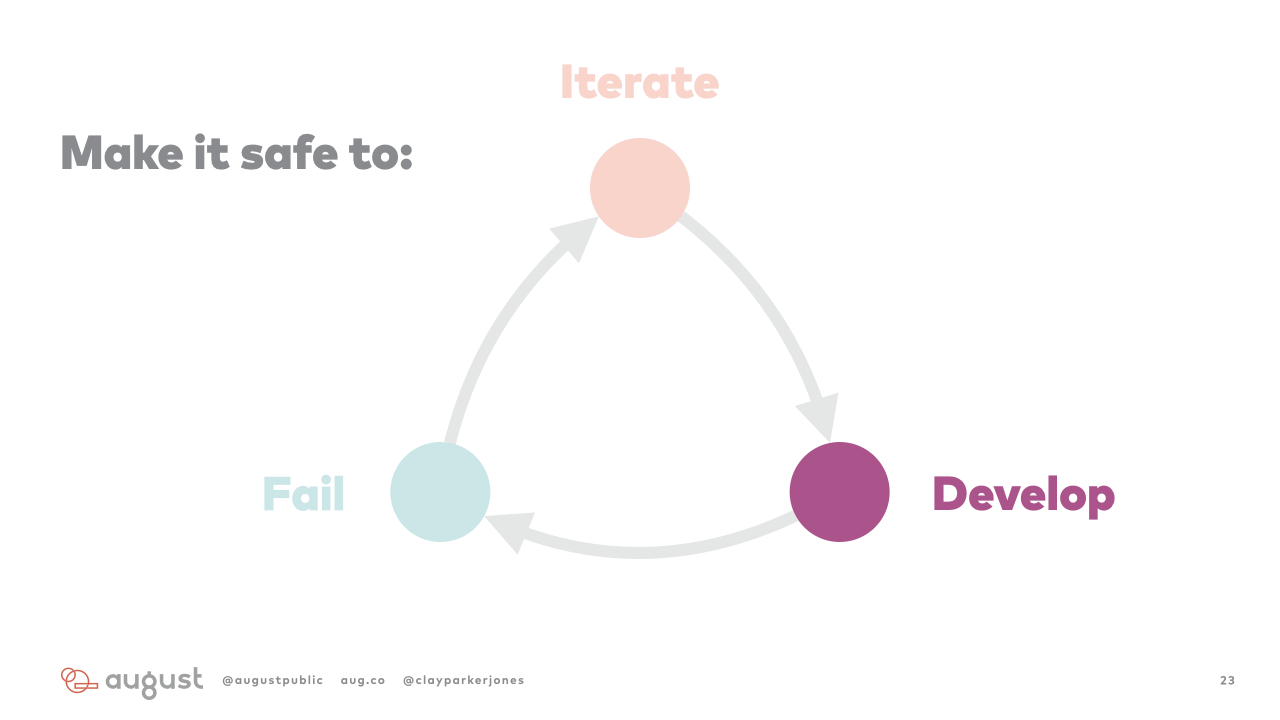

- Making it safe to fail within a team (failure begets learning)

- Making it safe to iterate within a team (continual release to customers)

- Making it safe to develop the team, organizationally (legitimate even over directed change)

My hypothesis is that these are sequential and self-reinforcing, but, we'll see!

This day is structured according to that loop, and we spend two hours on each. That time is spent with a quick story to illustrate or highlight the importance of each category, followed by a game, followed by a recommended new practice that makes this new thing safe. The game is there to set up the mind to try something different, or to show how the following practice might work in real life.

Section 1.5: Mindsets for the day

Before we get into that, though, there's a central tension in this work that is worth talking about: small experiments with radical intent.

Remember throughout the day that:

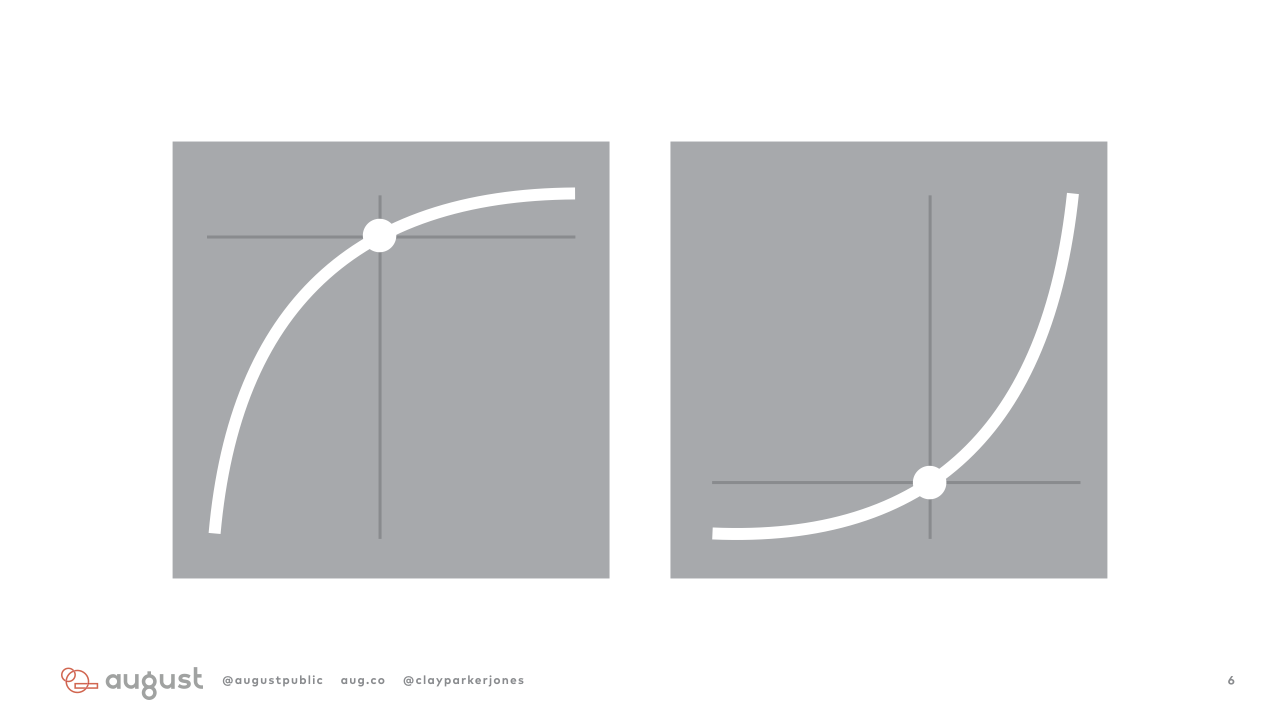

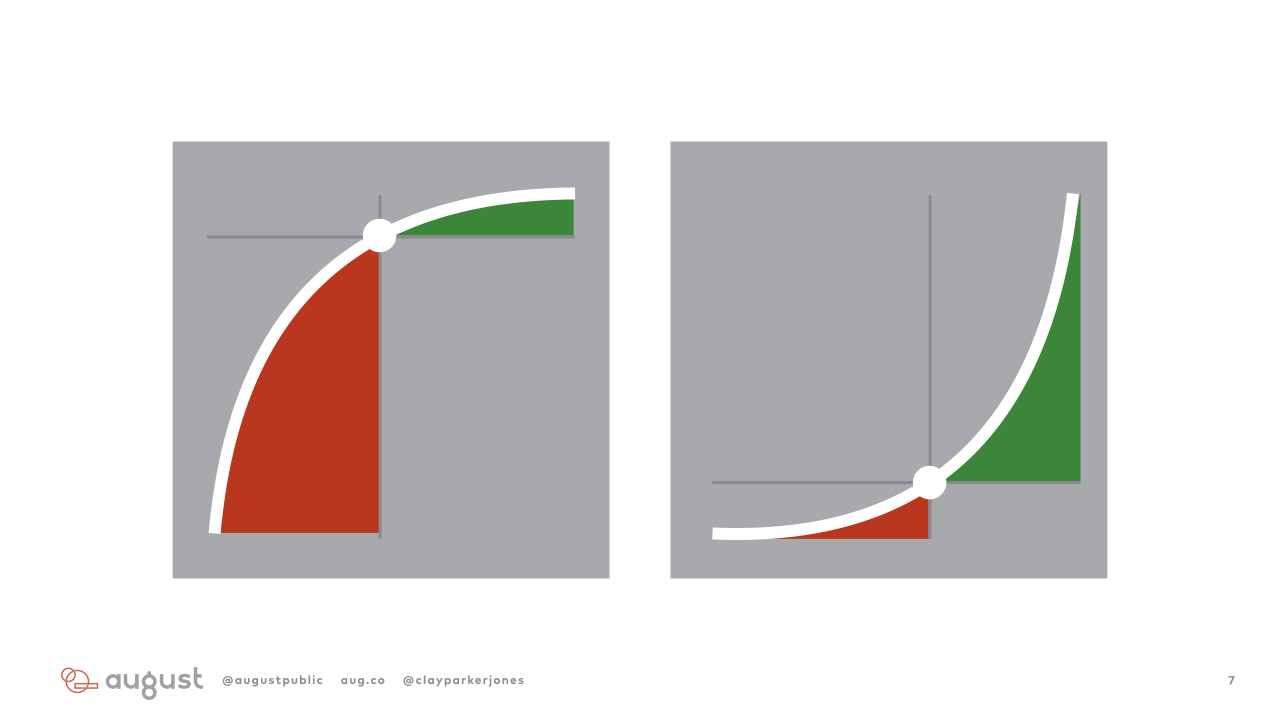

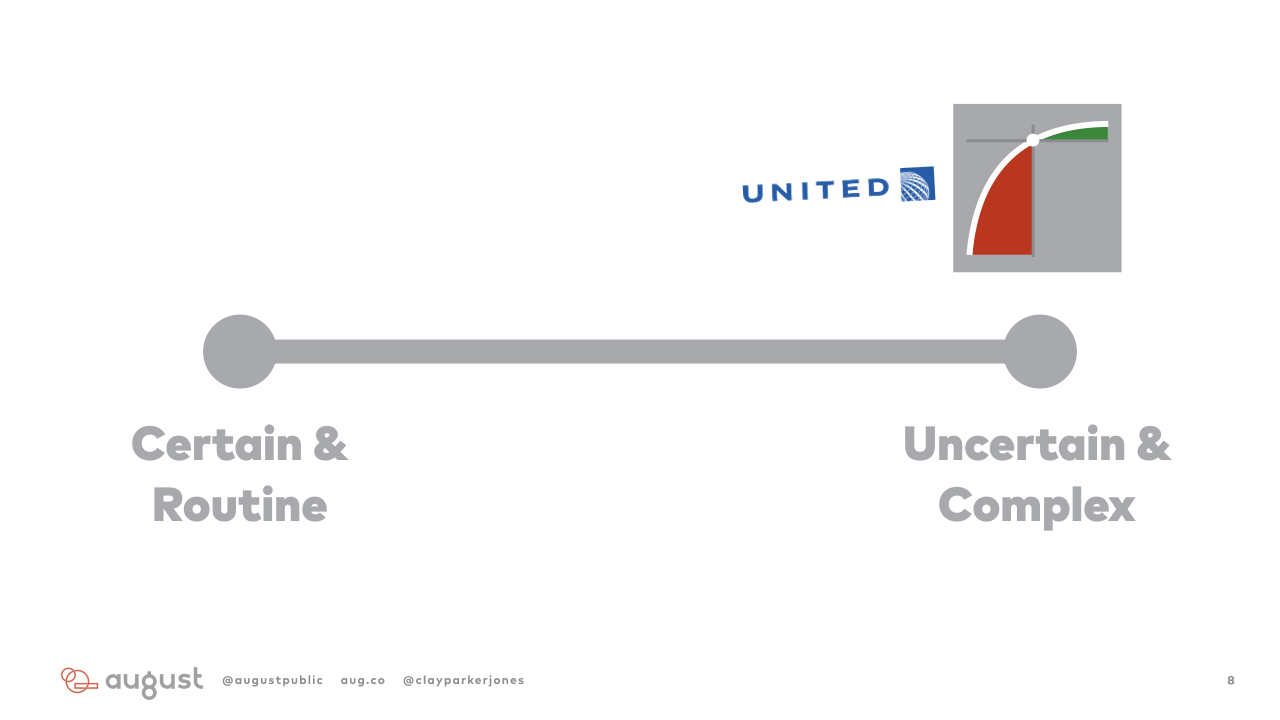

- Exponents are hard for humans to feel

- Your normal corporate intent will make iteration feel lame and small, so it's better to aim high

- Uncertainty is scary! It's better to make big bets safe

A quick discussion of Bezos' most recent letter, but you may as well just go read it.

Section 2: Making it Safe to Fail

Story: The hidden reason why GM's cars were so bad.

GM has a special test track in Arizona where execs are periodically flown to test new product. The engineers at the test track doctor the cars (hence "Ringers") for the execs. As a result, the execs are driving better cars than the public buys. The execs don't know about quality problems, and sign off on the new product.

Nuts.

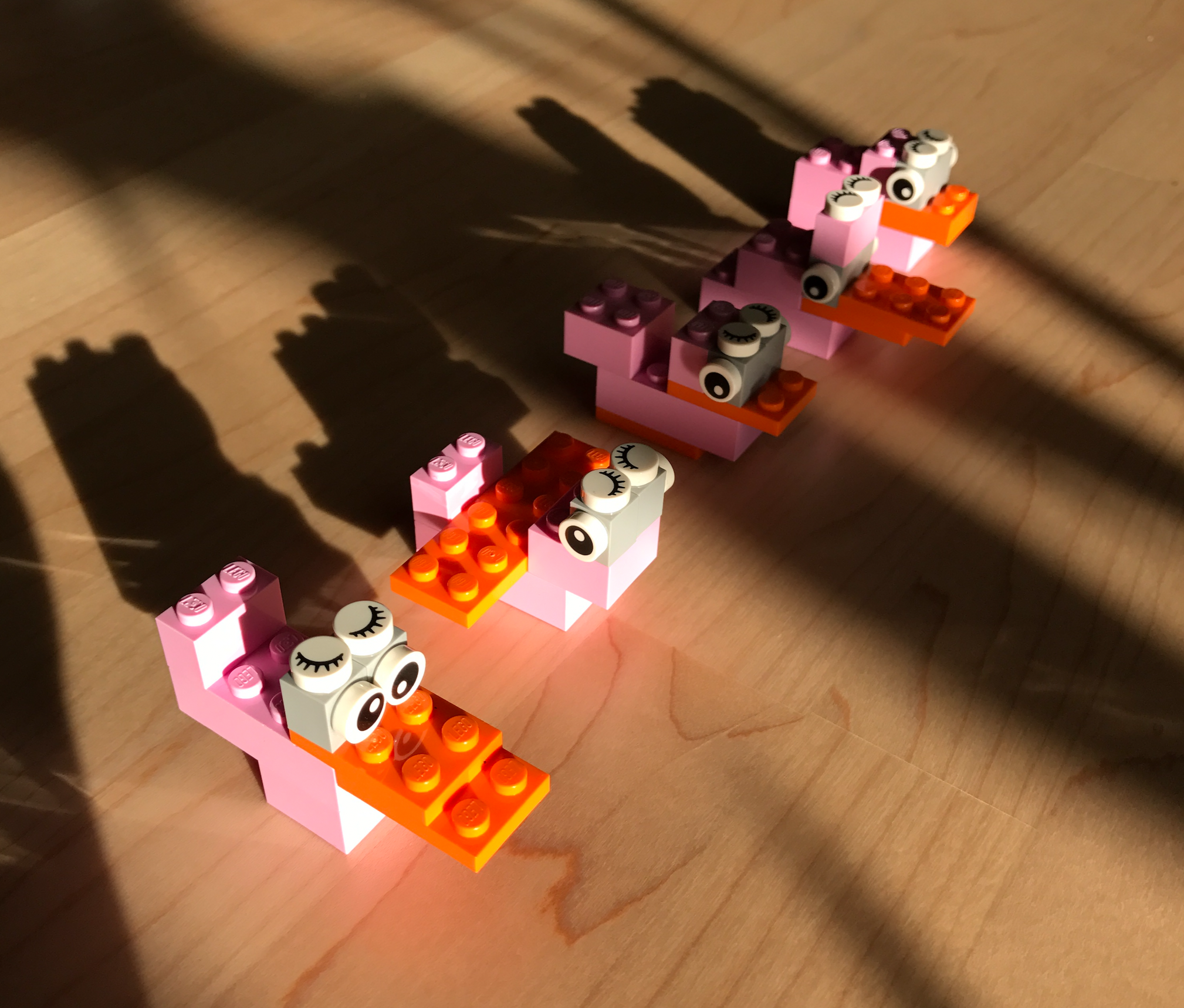

Game: Go Ducks.

- You give people a standard set of legos that can be made into a duck-shaped figurine, and ask them to make the best-looking duck possible in 2 minutes.

- Then you ask them to reconfigure their duck according to a strategy: Flying even over Floating.

- Then try the inverse of the strategy.

The neat thing is that all the designs end up looking the same. Thanks to Monique for this one!

Practice: a modified retrospective to generate Strategies.

Prompts (each with a two-minute silent writing moment):

- What’s working and not working for you about this team?

- What’s happening in the market that worries or excites you?

- What would you change if you could start from a clean sheet?

We then shared out in three rounds, and took five minutes to generate one or two strategies per person, which we read aloud, and voted on. The team leader proposed three to the team. The team confirmed that they wouldn't block the strategies, and then each person generated one change that they would make based on the strategies.

Section 3: Making it Safe to Iterate

Story: The Airbus A380 is the biggest passenger jet in the world, and it was a monumental engineering and logistics challenge to complete. When the folks building the fuselage went to install the wiring (designed elsewhere), they found that across 500+ kilometers of wire contained in the plane, they were two centimeters short (0.000004% off).

BANANAS.

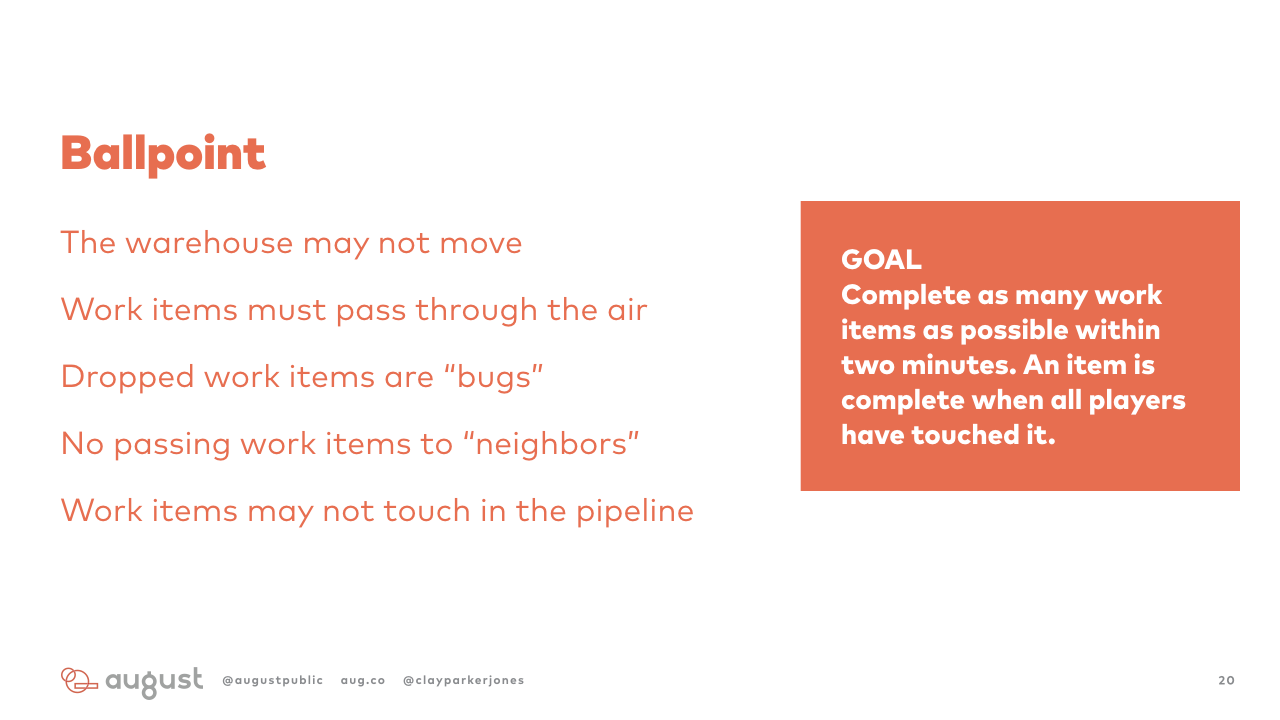

Game: Ballpoint. We play this one a lot at August. No spoilers on the solution, but it's a good one show people what rapid iteration looks and feels like.

Practice: Action. We then made the concept practical by applying the Action process – our radically simplified version of Action or Tactical meetings that you might have tried out there in the world. We built an agenda, using the changes that people wanted to make based on the strategies (from the first section), and then asked each person, "What do you need?" This took some radical ideas and made them super practical. They loved it!

Section 4: Making it Safe to Develop

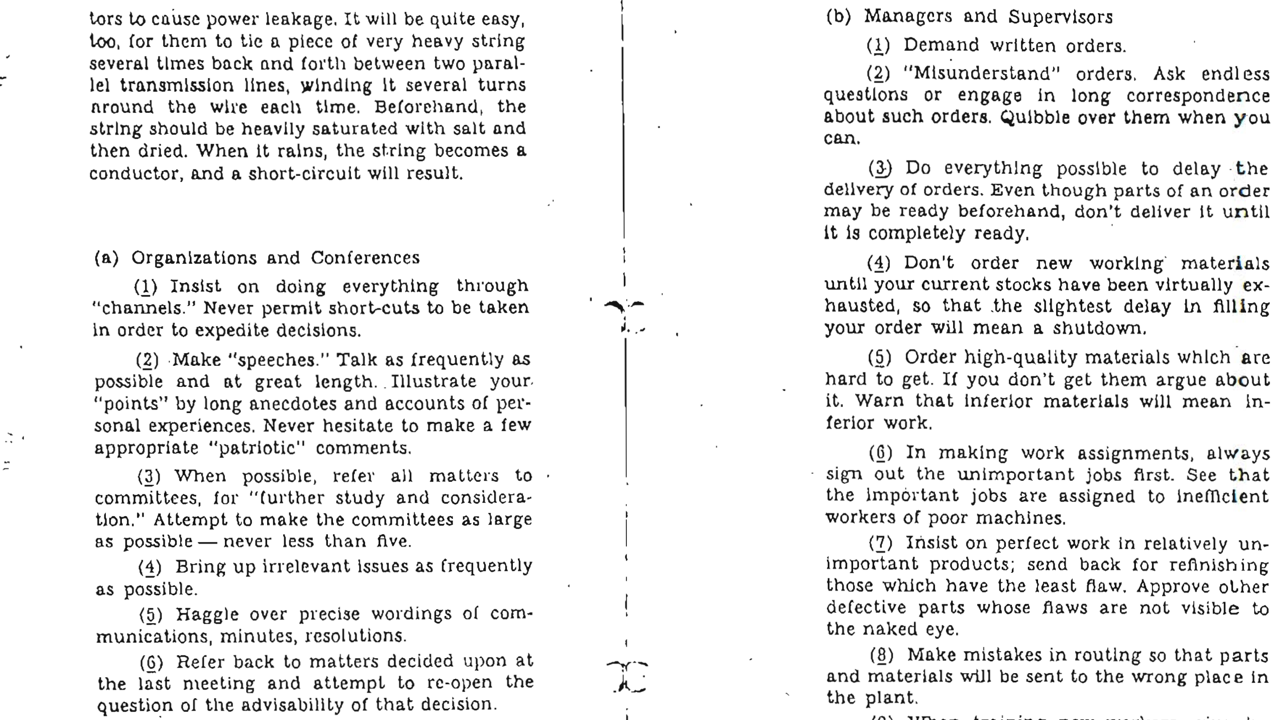

Story: Simple Sabotage Field Manual. Most folks reading this will probably know what this is, but I presented it in a bit of a different way. I put these slides up and asked, "What is this?"

"It's a set of instructions for work!"

"Seems super familiar!"

"That one – 'See that three people have to approve everything where one would do.' – is hilarious!"

...etc.

They're from a guide to simple sabotage, helping US collaborators sabotage organizations in "hostile" parts of the world.

We've normalized some really awful behaviors, haven't we?

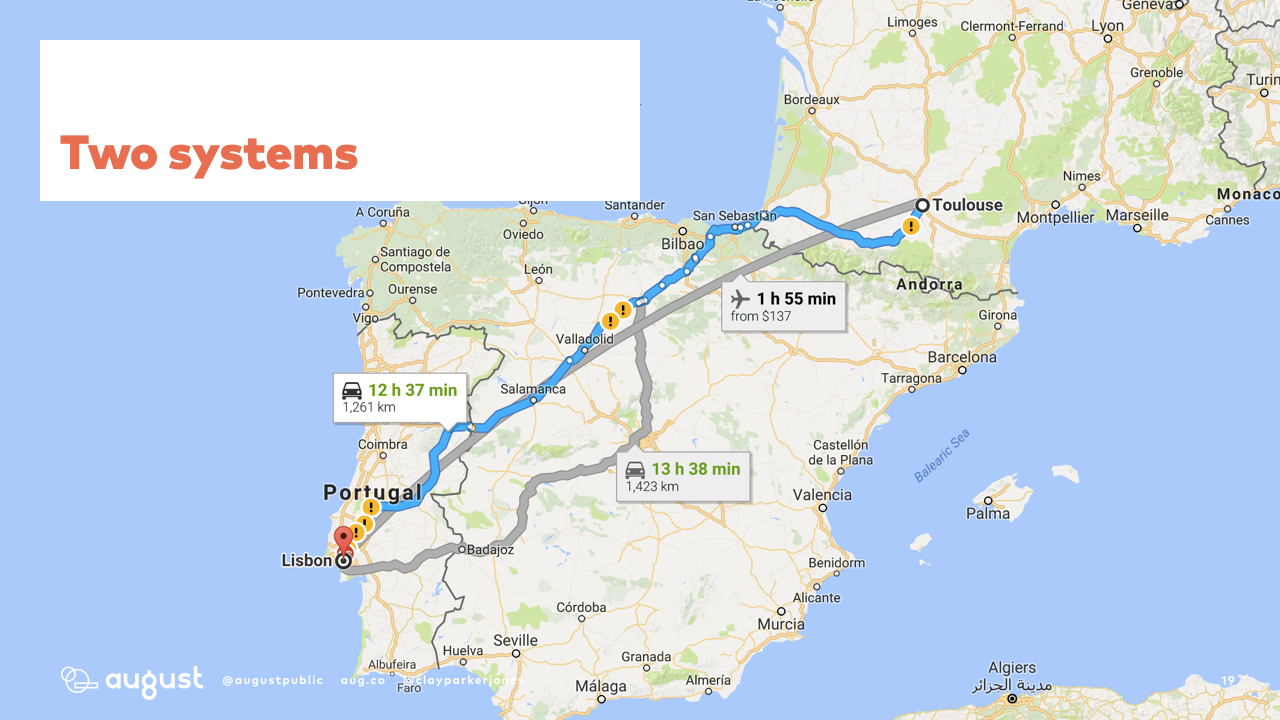

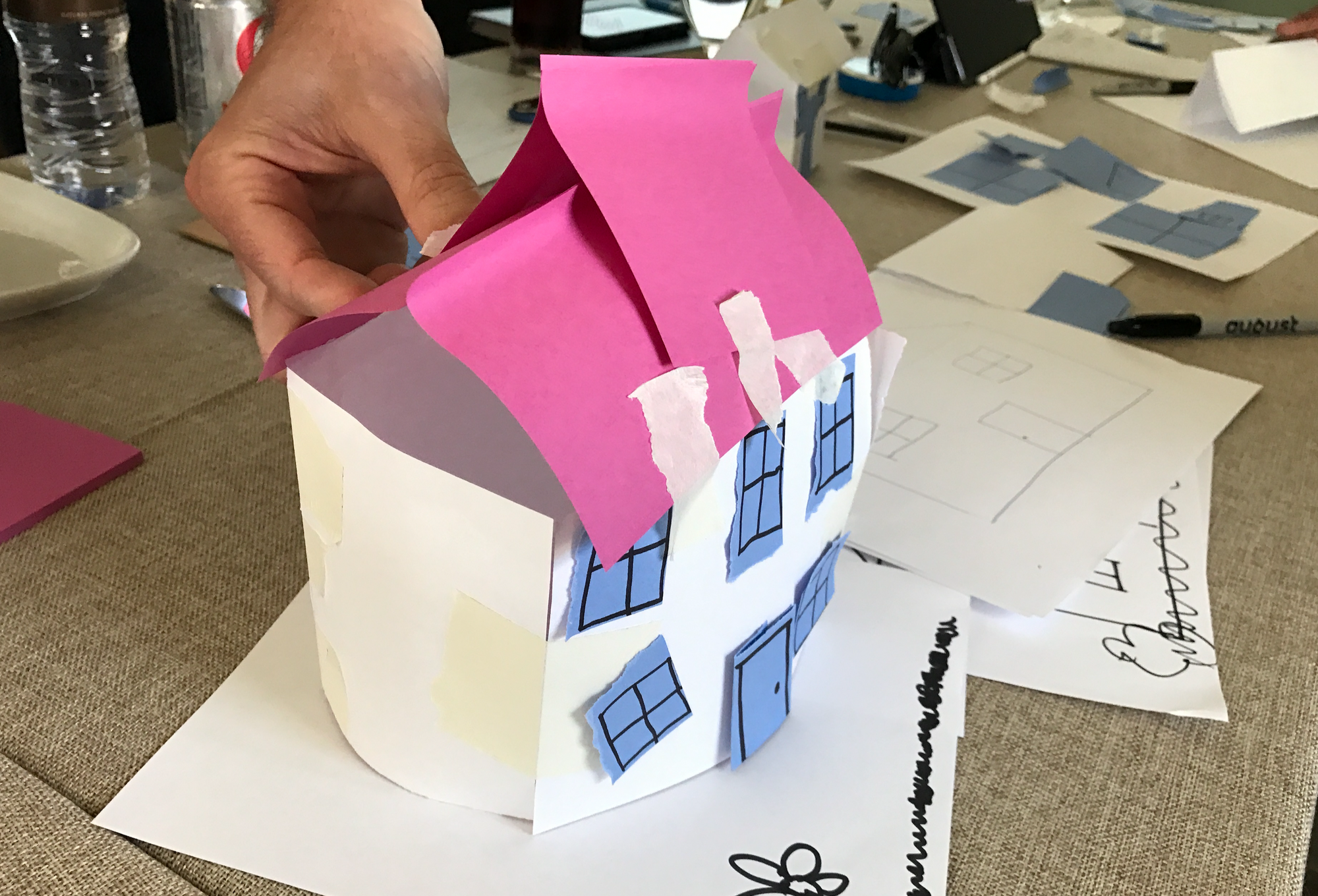

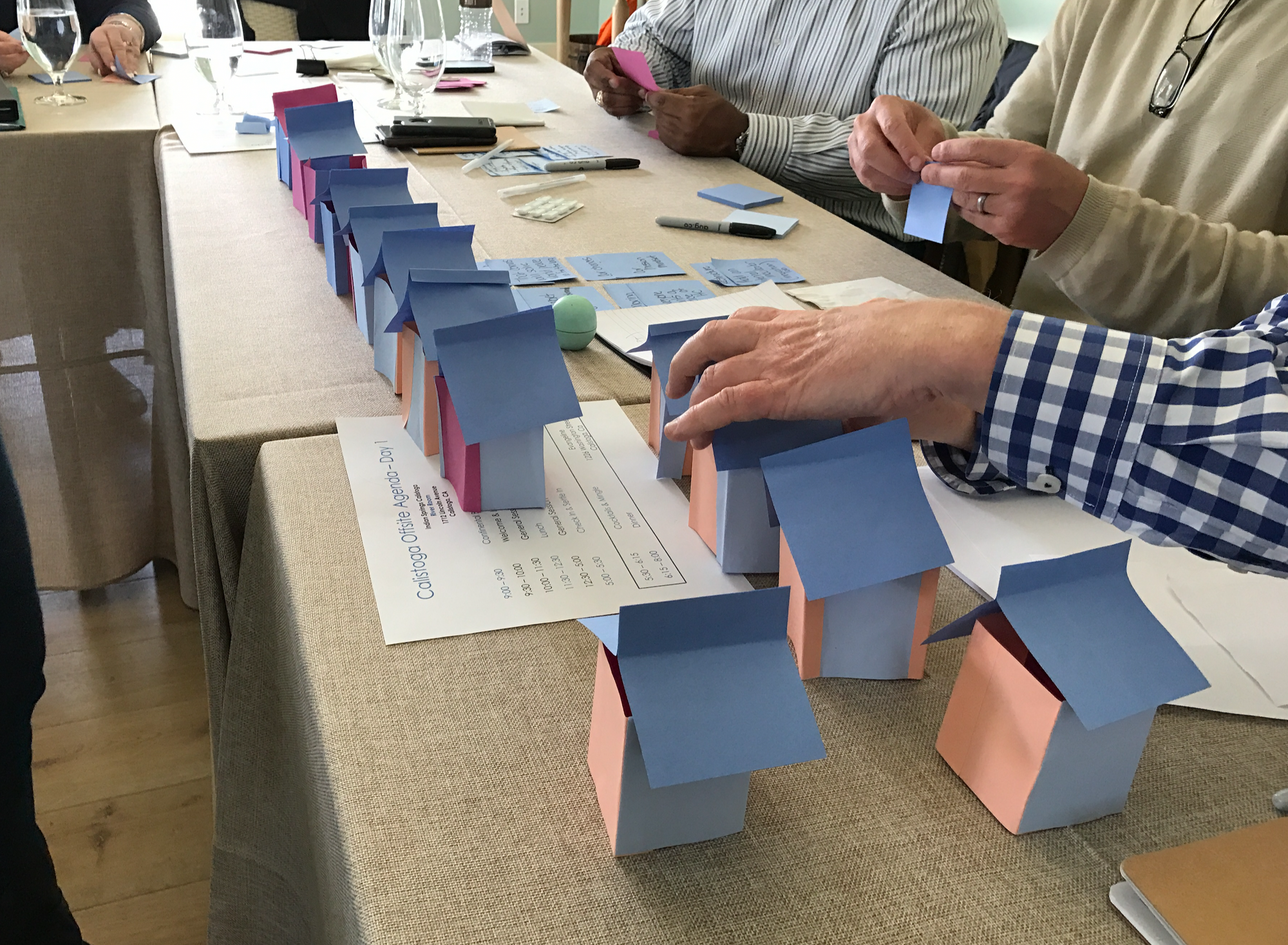

Game: Builders.

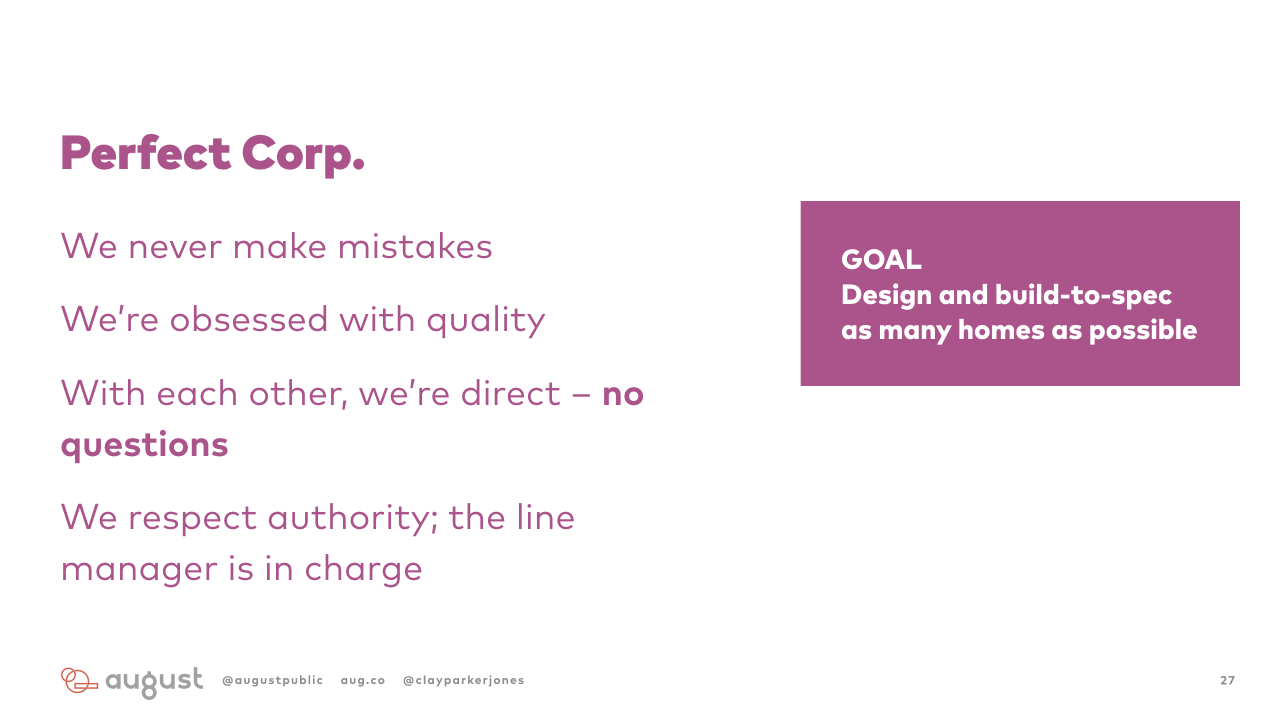

- You split the room into two teams: "Perfect Corp." vs

"Appreciative Homes," and give them identical building material, and an identical goal: Design and build-to-spec as many homes as possible. - Perfect Corp. gets their culture described to them as follows: We never make mistakes; We're obsessed with quality; With each other, we're direct, and we never ask questions; We respect authority, the line manager is in charge. Ask Perfect Corp. to appoint a line manager.

- Appreciative Homes gets their culture described to them as follows: The quality of our product comes from how we work together; We care about each other; We never give directions, we only ask questions; We all have autonomy.

- Put 10-15 minutes on the clock and let them get to work.

- Do not let Perfect Corp. ask questions of each other. Do not let Appreciative Homes make any statements to each other.

This is a really great juxtaposition of two really extreme ways of managing work. It's also suuuuuper fun for folks. This came to August in a recent Chem Test – but I don't know where it originates specifically. Let me know in the comments if you know!

On the left: the output from the Perfect Corp Team. I believe they finished two homes, and they weren't very much alike. On the right: the output from the Appreciative Homes team. They completed at least 13 homes, with very small differences between them.

Practice: Consent. We then went through a Consent process on two proposals, based on the biggest issues we dug up in the Action process. Lots of great learning for the team, with a fair amount of struggle.

My main takeaway continues to be that it's essential that teams start with a big, audacious proposal, rather than something that feels safe already. Start small and it'll feel like natural corporate incrementalism, not a small experiment with radical intent.

All in all, a great day that the team loved.

Comments